So how much power does the leader of the Australian Greens actually have?

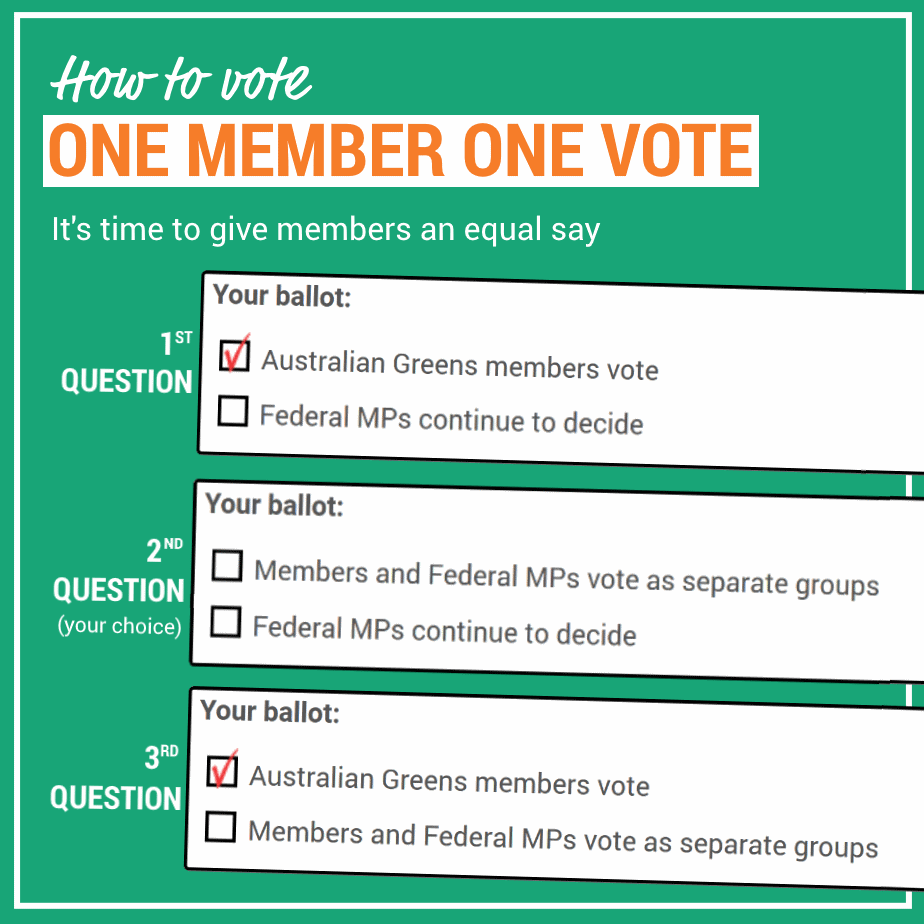

Greens members are currently deciding how we should select the leader of the Australian Greens. Should all members have a direct vote in choosing the leader, like in many other progressive parties around the world? Or should that decision be heavily influenced and controlled by elected MPs, like in the Australian Labor and Liberal Parties?

As an elected Greens politician, one big question that hovers perpetually in the back of my mind is: how can we ensure that as our party grows, we don’t make the same mistakes as other political parties?

How do we guard against the potentially corrupting influence of power?

How do we stay faithful to our core values while big corporations and the mainstream political system continually pressure us to betray them?

It’s a tricky question, without simple answers.

When you look at the history of progressive political movements across the globe, there’s an obvious general trend we need to avoid…

As parties win more votes and accrue more power, they gradually sell out - the leadership loses touch with the needs of the membership and the wider public, and falls increasingly under the influence of technocratic elites and other members of the political establishment. Eventually the party becomes a withered husk, clutching desperately to a radical past of standing up for social justice, while selling out workers, voting against climate action and locking up refugees in concentration camps.

For many Greens members, the push to democratise the movement by introducing free elections of the party leader is ultimately about guarding against all that. A “one member, one vote” system is intended to help ensure the party leadership remains as responsive as possible to Greens members, supporters and the wider general public.

Who does the leader actually ‘lead’?

The strongest argument offered against democratising is that the MPs themselves (also known as the ‘Party Room’) are best placed to decide who among them is the most capable of maintaining unity and consensus within the group, bringing the Party Room ‘Greens Team’ together and coordinating the most effective use of each team member’s skills and strengths.

This narrative of “The members of the team should decide who gets to lead the team” sounds very compelling at first glance, until you remember that the ‘team’ is not just the ten federal MPs in Party Room. The ‘Greens Team’ is actually a massive cohort of thousands of members around the country (including elected representatives at the local and state levels), and tens of thousands more Greens supporters and volunteers, many of whom would probably sign up as members if being a member actually gave you much meaningful power over important decisions.

Just because someone happens to be popular with at least 5 out of the 9 other MPs in Party Room doesn’t necessarily mean they are also the best person to lead and work with all the other Greens elected reps, state delegates, party office-bearers, members and supporters.

What’s the role of the leader?

Unfortunately, the discussion about whether we should have a one member-one vote system of electing the leader, or a 50-50 system where the MPs hold disproportionately more power, seems to be premised on some pretty significant misconceptions of the role of the parliamentary leader and Party Room as a whole. I would argue that these misconceptions have been inadvertently fostered by system insiders (i.e. some MPs and senior staffers) who don’t quite realise how much power they personally exert over the broader movement.

The party leader role has never been very clearly defined, and most Greens members don’t understand what the leader’s powers and responsibilities are.

Some people think a core function of the party leader is to facilitate and chair meetings of the Greens MPs within Party Room, but that responsibility primarily sits with the internal role of ‘Chair of Party Room,’ currently held by Senator Janet Rice. Similarly, another important internal leadership function - the role of ‘Party Whip’ - is currently held by Senator Rachel Siewert, who is responsible for coordinating between all the other Greens senators so they know when they’re needed in Parliament to vote on legislation etc.

If we are to have a sensible discussion about how the leader is selected, we also need some understanding of what the leader currently does and should do. If we actually had a democratic process to elect our leader, the election itself would serve to flesh out what members and MPs think the role of leader should be. Different candidates might articulate quite different visions and strategies for leadership, and that would be a healthy and constructive component of the election process.

But in the absence of all that, I thought it might be useful to sketch out just how much power and influence the Australian Greens party leader currently holds, in order to illustrate that the leader is not ‘just’ a spokesperson, or simply a meeting facilitator for a small group of 9 Senators and 1 House of Reps MP. In fact, the leader holds a huge amount of influence over messaging, policy formation, election campaign strategy, behind-the-scenes negotiations with other political parties (particularly in a hung parliament situation), and party resource allocation.

Staffing

In an organisation that depends very heavily on volunteers, the allocation and supervision of paid staffing roles can have a huge impact on the direction and success of the party. For example, you could choose to allocate staff to coordinate a community campaign against mining in the Pilbara, or to support a Greens by-election campaign in a strategically significant rural NSW seat, or to run a massive nationwide supporter education project that upskills newer Greens members on party policy and philosophy, or to mentor and support more Aboriginal candidates to run in the upcoming NT election.

Last year, as a Greens City Councillor, I was invited to speak on a couple of different nationwide TV and radio programs (on very conservative networks) about the climate justice protests. Apart from studying a few journalism courses in my undergrad uni days, I’ve never actually had any formal media training. Obviously a nationwide TV interview is not something you want to screw up. Luckily, one of Richard Di Natale’s paid staffers was permitted to spend twenty minutes on the phone with me to share some tips and strategic advice which I found quite helpful. Without the leader’s office allocating that little bit of staff time to support me in my work as a councillor, this task would have been a lot more difficult and daunting.

Every day, the leader’s office is making decisions like that – about where and how to allocate staff time – which impact the effectiveness of our elected reps at other levels of government, as well as members and volunteers.

How you use and allocate staff resources is a massive decision that dramatically influences what practical outcomes the party achieves and how well we do at elections. Parliamentary staff are often the ones doing the detailed research and drafting work to flesh out party policy positions and propose legislative amendments, but they can also get involved to a greater or lesser extent in election campaigns and volunteer coordination.

Currently, the Australian Greens leader has an allocation of 22 full time-equivalent (FTE) permanent staff in their office. The other Greens Senators (including Deputy Leader Larissa Waters) get just 4 staff each.

But it’s not so much the ratio of staff between the leader and the other MPs that we should be most concerned about... It’s the ratio between paid MP staffers, and the other paid roles within the party that are more directly controlled by the membership.

For comparison, outside election time, the entire Queensland Greens organisation usually has the money to employ just 2 or 3 FTE staff roles, who are mostly flat-out on basic administrative work to keep the party going. The NT Greens don’t have any paid roles. So in practical terms, a federal leader’s office with 22+ staff can get a lot more done, and have a very big impact on party strategy and policy.

I don’t know exactly how much each of those staff in the leader’s office are paid, but their combined salaries and associated costs would probably add up to a couple million dollars per year. So when you multiply that over a leader’s term (from one federal election to the next), the leader is making a decision to allocate at least $8 to $10 million worth of Greens resources without any direct accountability to the wider party. In contrast, whenever the Australian Greens allocates money from its party budget, the decision is subject to detailed scrutiny and debate from national delegates representing Greens members right across the country.

As the party wins more seats (and more staffer roles), the amount of power the federal MPs have over the party will necessarily increase, since they and their staff will have more paid capacity to influence policy and strategy than volunteers and grassroots members.

The decision about how best to allocate parliamentary staff roles is one of the most important decisions in the entire party, impacting not just the other federal MPs, but the work of thousands of members around the country. So it’s essential that whoever makes that decision (currently the party leader) is directly accountable to all the people who are impacted by it.

Policies and Deal-Making

The party leader subtly but directly shapes party policy far more than most Greens members probably recognise. In the Greens, party policy is theoretically written and controlled by the members themselves, through a tiered system of branches and policy committees, with eventual sign-off by state and national councils.

But the practical reality is that the policies which are produced by the volunteer committee system – available online at https://greens.org.au/policy - are necessarily quite vague.

Using consensus-based decision-making to allow thousands of volunteers input into party policy takes time, and can’t be rushed without disenfranchising people. So you either:a) write very detailed policies, which take a long time to produce, running the risk of the policies going out of date in a short time-frame due to changing external factors, orb) keep the policies very general and open to broad interpretation, trusting that when our MPs are voting on legislation or drafting their own bills and amendments, they will keep faith with the aims and principles decided by members.

The Greens tend towards option b), which means the policies are often a little too ambiguous to be much use for election campaign communications, and sometimes don’t offer much clear guidance to our MPs when they’re making decisions.

As a result, the party now has a parallel process to develop ‘policy initiatives’ for each election campaign – currently available online at https://greens.org.au/policies (note the slight difference in web address) - which are more specific and detailed. These are the ‘policies’ that get announced to the media and appear on Greens flyers and websites during an election campaign.

Decisions about which policy initiatives to prioritise and what goes into them are very heavily influenced by the leader’s office and the party room. Because of how time-intensive this kind of detailed policy drafting is, these policy initiatives are primarily written by MPs and their staffers, and although they are theoretically signed off by the Greens’ National Council, the process is much more rushed and isn’t open to widespread member participation.

So by virtue of controlling lots of staff who end up writing the initiatives (and maintaining the website etc), the leader of the Australian Greens exerts a huge amount of personal influence over the policy platform that we take to an election – arguably much more influence than the leaders of other Australian political parties do (with the possible exceptions of One Nation and Centre Alliance).

Crucially, the party leader also has a lot of control over deal-making with other parties. As explained above, our party’s published policies are quite vague, and it’s not uncommon for our MPs to have to vote upon issues where our policies aren’t specific enough to give much guidance. In such cases, Party Room – led by the Parliamentary Leader – makes these calls with little reference to the views of the wider Greens support base.

Even where we have a clearly stated policy goal in mind (e.g. Net Zero Carbon Emissions by 2030), there are important strategic decisions to be made about when to make compromises and support or oppose imperfect legislation that might get us halfway to that goal. The decision not to support Rudd’s 2009 Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme is a notorious example of this kind of strategic call, but another more relevant example from 2017 is the internal Greens debate about whether to support Malcolm Turnbull’s very weak ‘pseudo-Gonski’ education funding proposal. At the time, Greens members around the country who felt strongly about the decision realised to our dismay how little direct influence we had over such an important decision. Because Richard Di Natale’s leadership did not depend on a majority vote of Greens members, there wasn’t much practical incentive for him to worry too much about what the thousands of Greens members actually wanted, as long as his decision had the support of at least 4 of the 9 other MPs in Party Room.

Perhaps more than anything, it’s moments like these that illustrate just how important and powerful the role of leader is within the Greens. They’re not just a friendly face for the media. They are the key voice in make-or-break decisions that profoundly impact the entire Greens Team (i.e. the entire party membership – not just the 10 members of Party Room).

Yes, it’s probably true that the federal MPs themselves have a better sense as to who among them will be the most effective team leader and consensus-builder within Party Room. But even if that’s the case, if the leader of our party is haggling with other parties and making big, time-sensitive decisions about whether to support or oppose a crucial piece of legislation, I want the leader to care - at least a little bit - about what members like me think of the decision. And the best way to make sure they care is to make sure every single member gets an equal vote in choosing them as leader.

Messaging, Media and Comms Strategy

Regardless of whether we want this to be the case or not, when the leader of the Australian Greens speaks, they are understood by the media and broader public as speaking on behalf of the Greens – not just on behalf of the 9 other federal MPs, but on behalf of all the State MPs, local councillors, party office-bearers and grassroots branch members. So what they say (and how they say it) really matters.

A couple of years ago, I was involved in advising on strategy for an election campaign in Queensland. We’d decided on some quite nuanced messaging about phasing out coal mining which we knew worked well for the voters we were trying to win over. We’d put it on our flyers and social media posts and briefed all our Queensland candidates about how best to approach this complex issue. But then the federal Greens leader at the time made statements in a national press conference that completely cut across and undermined the message we were trying to convey. All the work we’d done as campaigners on the ground in Queensland to change the way the Greens were perceived was undone by a single speech made by a leader from down south who hadn’t visited Queensland for months and wasn’t directly accountable to Greens members.

Moments like this taught me that public spokesperson roles are incredibly powerful. Even as a local councillor, I can toss up a social media post or shoot a Facebook Live video and say something that impacts how the Greens as a whole are perceived. The stakes are way way higher when we’re talking about the leader of the entire federal Greens Party.

When the leader says something to the media, or sends an email to tens of thousands of people on the Greens mailing list, they can either reinforce or undermine the work of Greens employees and volunteers all around the country.

Obviously, we don’t want a system where dozens (let alone thousands) of Greens members are all trying to collaboratively write a media release or direct a video for social media. When timeframes are tight, such work necessarily has to be delegated to a small group of people. That makes sense to me. But what’s important is that the people who are doing this work and making these decisions are accountable for them.

We need to build a culture within the Greens where our federal spokespeople in particular are attuned to our party’s diverse and varied needs (and messaging strategies) around the country, and understand intuitively that what works well as a talking point in Hobart might not resonate as well in regional Queensland (and vice versa).

Right now, an MP can become leader of the party by winning a senate preselection in their own state, and then winning the majority support of the other MPs in Party Room. They can end up speaking for Greens right across the country, without ever needing to have a conversation with rank-and-file Greens members from other states, or taking the time to understand what’s important to Greens supporters (and swing voters) in different parts of Australia.

Our party leader’s control over messaging and comms includes the use of large nationwide email lists. Decisions about when to send out a nationwide email requesting donations, for example, can have a big impact on supporters’ attitudes to the party. It obviously makes sense that a party leader can email their members directly. But we need to acknowledge that the ability to send a mass email (or post a tweet or a video) to thousands of supporters carries with it a great deal of power and responsibility.

Holding power to account

The above elements I’ve unpacked are not an exhaustive list. They’re just samples of the kinds of big decisions over which our party leader exerts significant control.

Reasonable people can disagree about who in a party should have control over certain decisions. Right now, some decisions are made unilaterally by the leader, some decisions are made collectively by the federal Party Room MPs, and some are made by national council delegates, or by individual staffers, or by local branches, or even by a vote of the entire membership.

What I’m seeking to show with the above ramblings is that right now in the Greens, the power over a lot of big important decisions is actually quite centralised in the hands of federal MPs and the leader in particular. I’m not necessarily saying that’s a bad thing. But we need to recognise this heavy centralisation, and understand the importance of holding that power to account as our party grows.

One of the key reasons decision-making has become so centralised in the Australian Greens is that there are very few formal mechanisms within the party which force the leader to pay close attention to what members on the ground are saying.

Politicians have a lot of competing demands on our time and attention. We get literally thousands of emails and calls and social media posts from corporate lobbyists, NGOs, well-connected individuals, random members of the public, and party members.

When you don’t have time to pay attention to absolutely everyone, you gravitate towards the people who have the most power to influence whether you remain in your position.

The thing is, once you’ve been elected as a Greens senator or federal MP, you’re pretty safe within your own party. It would be extremely unusual for party members not to preselect you as a candidate for the next election, even if a lot of members are unhappy with some of the decisions you’ve made. So without even realising it, you gradually spend more time listening to lobbyists, technocrats and conservative media commentators than to your own members. Giving elected MPs disproportionate influence over the choice of party leader (such as with a 50-50 voting system) doesn’t counteract this problem, and in fact reinforces it.

Grassroots Democracy is what makes the Greens different

The choice between a one member-one vote system or a 50-50 system for choosing the leader is fundamentally a question of how much power we want members and other office-bearers to have over the direction of the party, and how much power we want to leave purely within the hands of our federal MPs.

For better or worse, the party leader is a very very powerful position. A 50-50 voting system means the choice of who leads the party would continue to sit primarily with our federal MPs. Long-term, as the party grows, this would create fertile ground for factional infighting among MPs, and the sort of dirty power games we see in the Labor and Liberal parties.

On the other hand, a one member-one vote system would still give MPs the ability to make public statements about who they think should be leader, while giving members meaningful control. This would make the party leadership much more responsive to the rest of us, while also ensuring the successful candidate has a very strong democratic mandate for the direction they want to take our party in.

Most other Greens parties and progressive parties around the world have a one member-one vote system to elect their leader. It’s time the Australian Greens followed suit.

Further reading:

Open letter from Greens members supporting One Member, One Vote

A post by Tim Hollo, former Communications Director for Australian Greens Leader, Christine Milne

Member discussion