Establishment vibes: Do 'extreme Greens' criticisms hit harder when we're no longer 'doing politics differently'?

This is a reworked, more detailed version of an article first published in the online journal Green Agenda. Thanks to the Green Institute for continuing to support and provide a space for critical analysis and commentary about green politics...

I've always had a sweet tooth, but even I have my limits for sugarcoating.

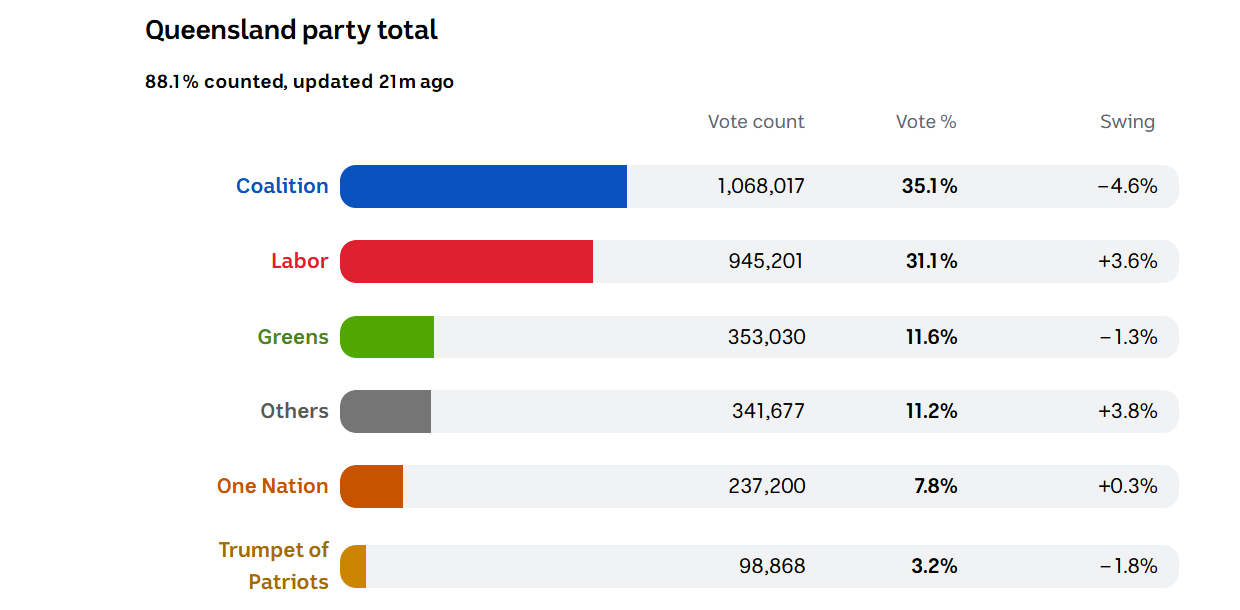

The Greens' 2025 federal election result certainly wasn't disastrous, but it was undeniably a step backwards, especially on the back of recent, mediocre state election results (particularly in Queensland).

We have to learn from this, and go deeper than the headline explanations.

Yes, a few progressive voters in key seats switched to voting 1 Labor, 2 Greens because they thought this was the best way to keep out Dutton.

And yes, we only lost in seats like Melbourne and Wills because the collapsing Liberal vote pushed up Labor's primary vote enough that they could win on preferences.

But the Greens primary vote also fell in seats where the benefits of incumbency – bigger platforms, more time and resources to skill up volunteers and reach people – should have led to our vote increasing.

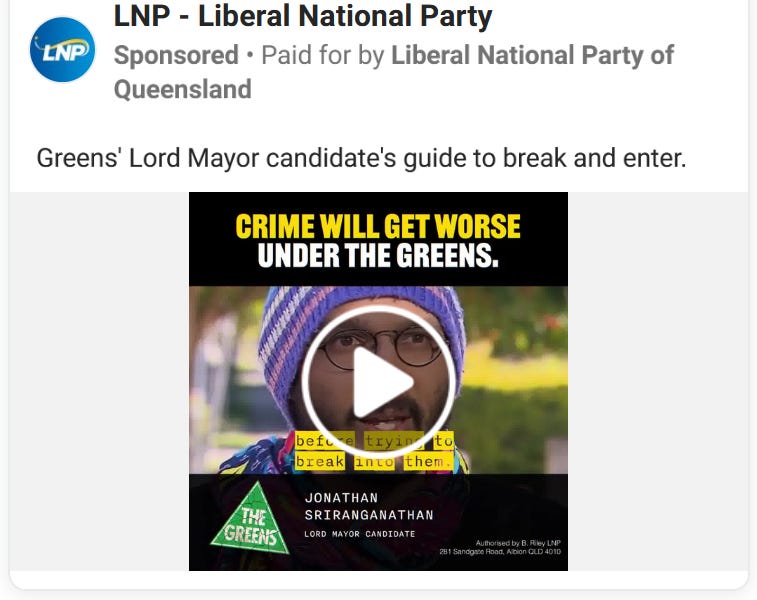

The sustained, combined attacks from both major parties, multiple right-wing minor parties, cashed-up oligarch-funded entities like Advance Australia, and several prominent mainstream media commentators were clearly a major factor.

I've written previously about my own experiences with the dark magic of asymmetrical smear campaigns. Spend enough money on targeted propaganda and you can distort people's perceptions of reality.

While political smear campaigns between the major parties are common, the Greens are significantly more vulnerable because we have far less reach and fewer resources to counteract them. But recognising all that isn't especially comforting when you remember that the eye-watering sums deployed to attack and delegitimise the Greens this election are still only a tiny fraction of what billionaires and big corporations could spend on campaigns and lobbying if they really felt threatened.

In my local electorate of Griffith, Greens MP Max Chandler-Mather worked his arse off for three years. He was an effective media and parliamentary communicator who succeeded in elevating key issues on the national stage. And on the ground, he and his office staff also performed at a high level, not only in terms of one-on-one constituent advocacy, but also in running regular community dinners and school breakfasts, and supporting local campaigns within his electorate. In fighting off the Gabba Olympic stadium proposal, he even helped save East Brisbane State School from being shut down.

Yet his impressive local track record wasn't enough to outweigh the attacks against him. The same was true of our other federal MPs, and indeed hardworking state MPs like Amy MacMahon and Michael Berkman, who both experienced negative swings in Queensland's 2024 state election.

When using conventional campaigning tactics and channels (I now include centrally-coordinated doorknocking and social media posting as “conventional”), for every person we reach with a message, our political adversaries are reaching ten.

One lesson we should take from the poor results in May 2025 is that we can’t out-perform the political establishment’s attacks against us when we play by their rules and conventions.

We face a frustrating quandary: Australian Greens policies and strategic approaches are far too conservative to meet the urgent need for deep systemic change, yet a significant proportion of voters still seem to consider the party “too extreme.”

Our policy platform has barely changed since 2022, but some voters’ perceptions of us evidently have. To respond by treating that “extremist” criticism as valid would be giving mining billionaires, property speculators and weapons manufactures exactly what they want.

I guess we're all extremists now

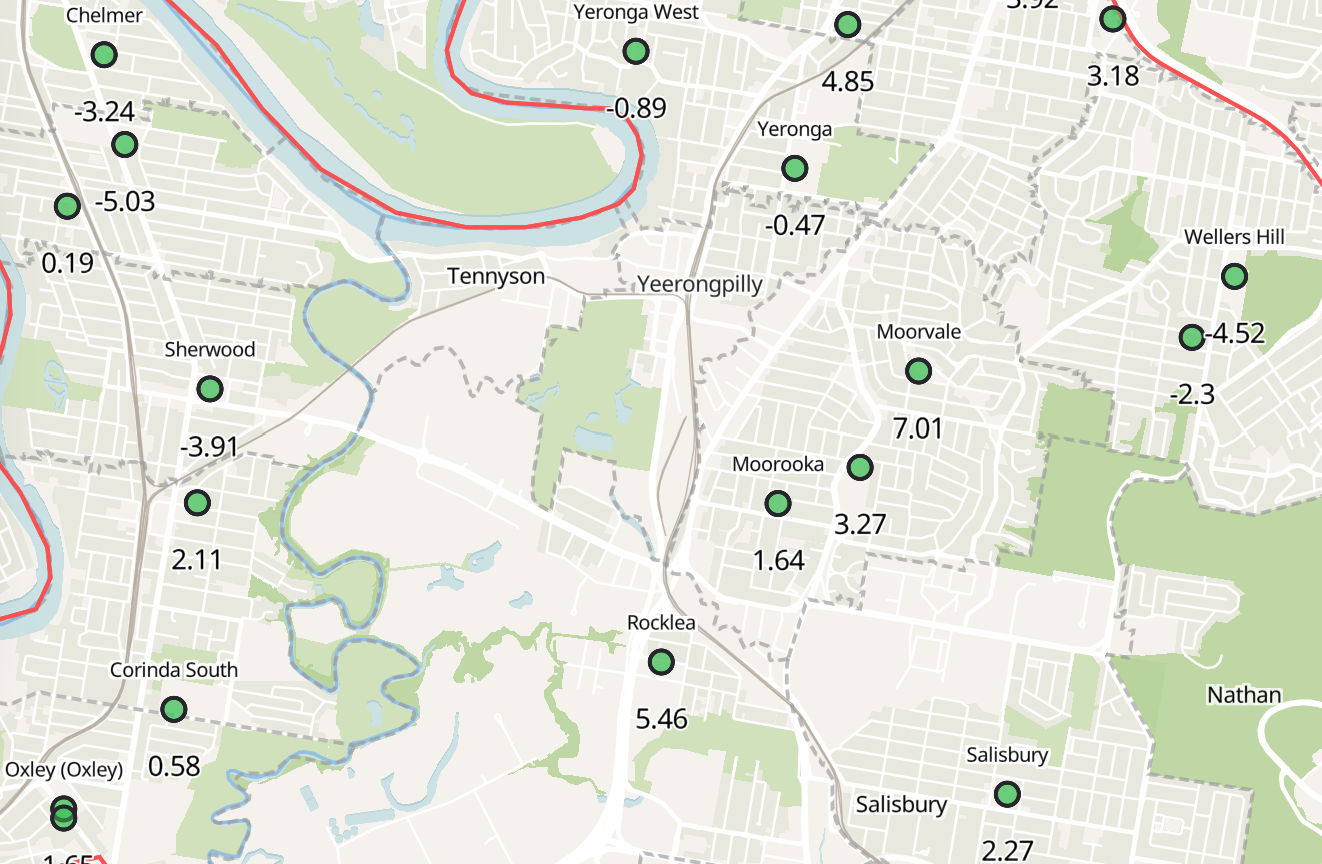

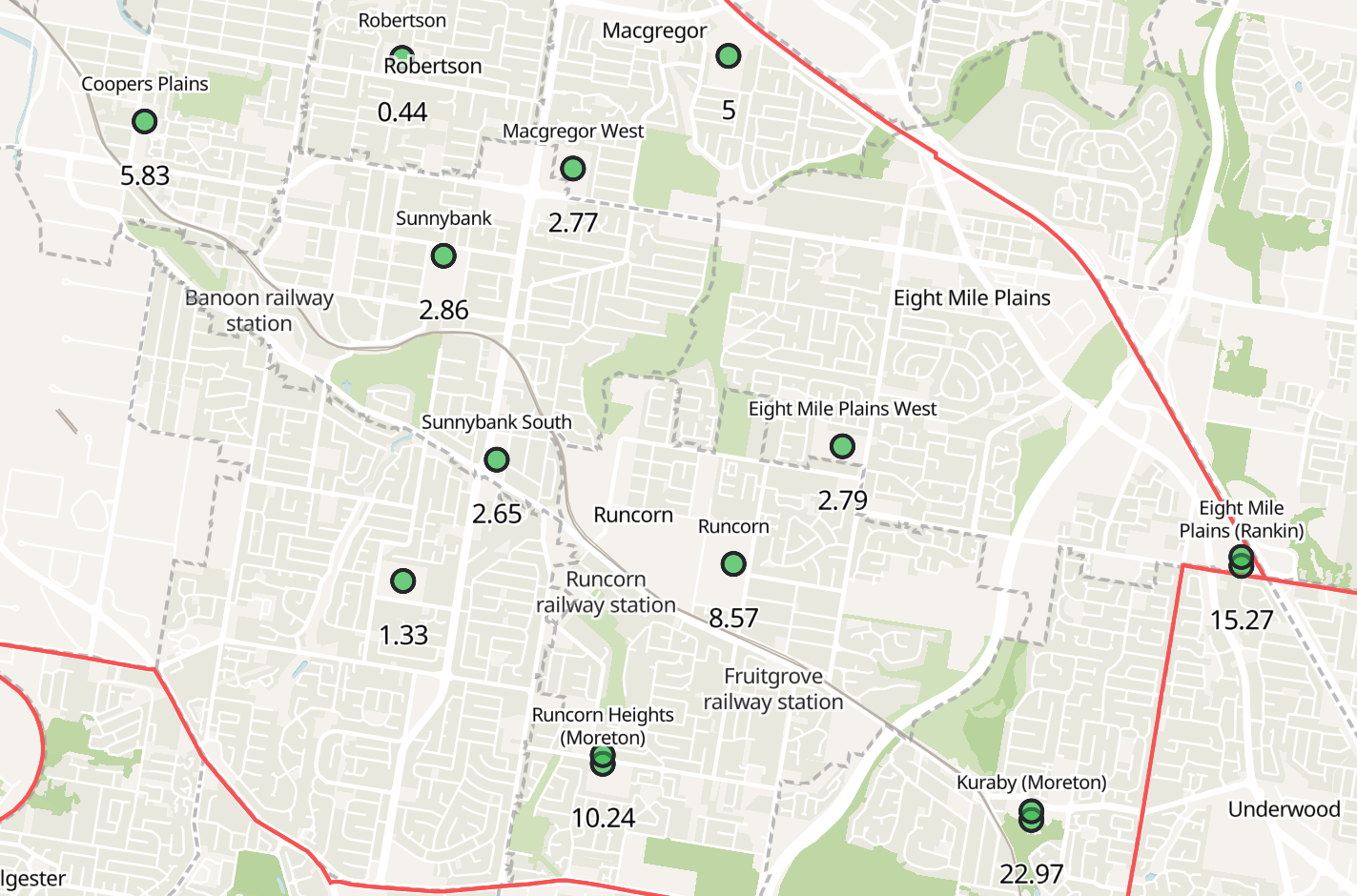

This election, I spent most of my time on Remah Naji's Moreton campaign. Polling booth data shows that while Remah swung a lot of votes in poorer and more culturally diverse parts of her electorate, it was obvious that the Greens reputation as 'extreme' also turned some voters away from her, particularly in the most affluent neighbourhoods.

While the Greens suffered negative swings in the most affluent parts of the Moreton electorate - Wellers Hill, Sherwood etc. - Remah Naji attracted large swings in the southern booths, where average incomes are lower and more people speak languages other than English

“Too extreme” is a conveniently ambiguous attack framing that allows different people to amalgamate and substitute their own pet grievances.

For some, “extreme” means solidarity with persecuted minorities, whether that’s trans folk, refugees or First Nations people. For others, “extreme” apparently means saying “hey, maybe we shouldn’t send weapons to a country that’s systematically bombing hospitals and schools.” Even calling for modest housing reforms that would bring Australia into line with many western European countries is supposedly extreme.

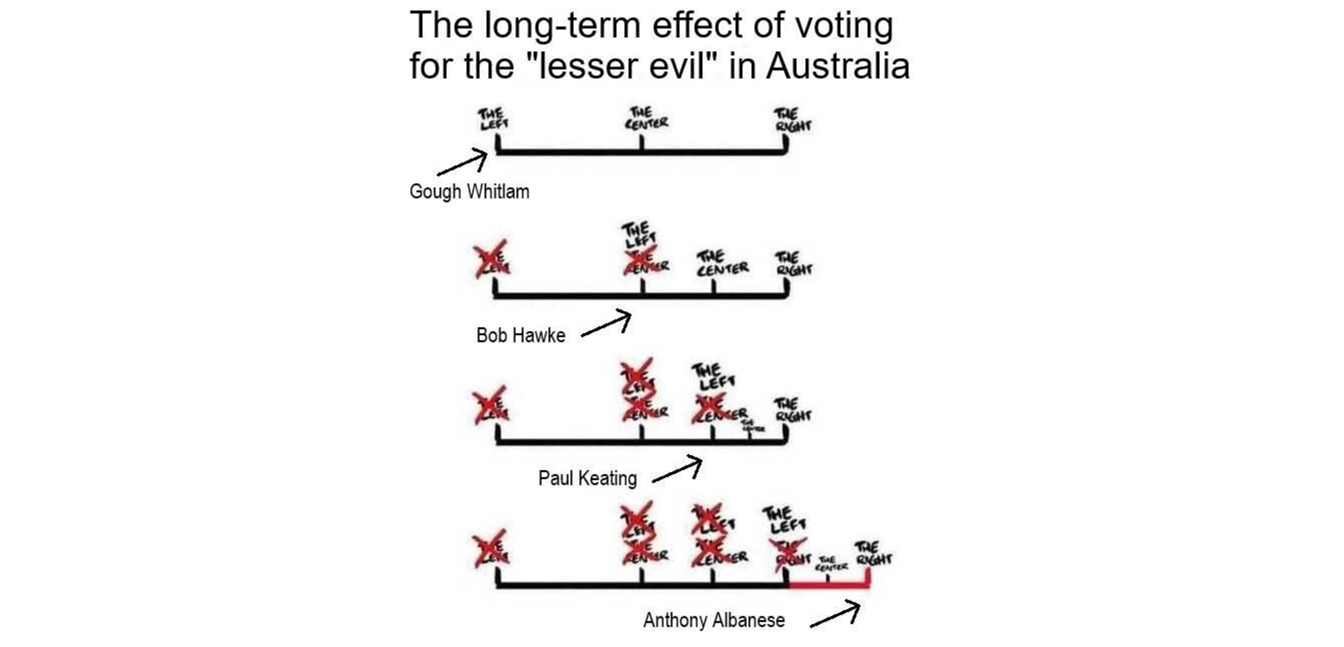

Those who profit from maintaining the status quo have branded the Greens 'fringe,' 'radical' and 'extreme' since the party’s inception. In response, we seem to have gradually watered-down our calls for change.

In the recent federal election, key party spokespeople barely mentioned Aboriginal land rights or the ongoing persecution of refugees. Even our main climate action demand buried the most important objective – our messaging de-emphasised our very moderate, science-backed policy goal of ending all thermal coal exports by 2030 (five years too late in my opinion), and focused only on banning new coal, gas and oil projects.

The party’s 2025 headline campaign narrative – fund social services and cost of living relief by introducing a slightly higher tax rate for the largest and most profitable corporations – was deliberately chosen to have broad, mainstream appeal. And indeed, most voters I spoke to on the ground in Brisbane’s south side were hard-pressed to identify anything in the Greens’ actual list of key policy priorities that they disagreed with or objected to.

Anyone who argues that the party’s core messages were “too radical” either hasn’t been paying attention, or is deliberately trying to scare the Greens into submission.

We already know the dangers of always uncritically meeting people where we think they’re at. We know where endlessly moderating our policy demands to satisfy industry lobbyists and oligarchs ultimately leads to – the modern Labor party. If our desired destination is big, positive change, that’s a dead end.

Did we back down on key struggles?

From a conventional election strategy standpoint, the Greens’ 2025 federal campaign made a couple of obvious errors…

In the last term of parliament, we rightly picked a big fight on housing, winning new supporters and increasing our political relevance. Similarly, our solidarity with Palestine was clearly a major friction point with the political and media establishment.

Both these issues represented strong, positive points of difference between the Greens and the major parties, and both were being used as flamethrower fuel by our political adversaries. But spooked by state election disappointments (I assume), the party leadership de-emphasised housing and Palestinian solidarity during federal campaign itself, retreating to 'safer' (but less interesting) terrain like healthcare, where the differences between Labor and the Greens weren't as obvious to less engaged voters.

The Greens should have defended our positions on housing and Palestine more proactively, challenging the major parties on their support for ever-growing house prices and their unwillingness to directly criticise Israel’s genocide. By backing off, and not sufficiently educating our own supporters to rebut propaganda and misinformation, we allowed our adversaries to reframe these issues in ways that made the Greens look like the unreasonable ones.

Having said that though, even if our top-level messaging focus this election had been different, I’m still not sure it would’ve changed the overall outcome dramatically, because the Greens remain shackled by a deeper tension that we’ve refused to grapple with head-on…

Extreme perception vs establishment reality

Is our long-term goal system change, or system tweaking?

If it is system change, do we look credible when we try to downplay this goal, and cast ourselves as mere reformists, even as our political opponents argue the opposite?

Here's where we might need to backtrack and find another route through the forest.

'Extreme' is all about perception. It's a subjective, relative descriptor that's easily thrown around without any basis in reality.

But whatever voters' perceptions might be, the material reality is that the Australian Greens are in many respects acting more and more like an establishment political party.

Gradually, over the years, our movement has sanded off our rough, radical edges in order to appeal to an imagined conservative centre, with little to show for it. Just like major party politicians, Greens MPs now spend big on billboard advertising arms races, wear suits into parliament, and respectfully engage in mainstream media forums and interviews as though the parameters of debate have not been heavily constrained and controlled by corporate interests.

Adam Bandt and co. have sought to position the Greens as a centre-left social democratic party, further left than the aspirations of some centrist reformist Greens, but still several steps short of full-on system change (and perhaps not as compelling for those of us with legitimate critiques of centralised top-down government).

However, party leadership has largely neglected to meet the growing public appetite for unequivocally anti-establishment politics, leaving most voters (and even members like myself) uncertain about whether Greens MPs aim to fundamentally transform the current system and tear down unjust hierarchies, or simply replace those at the top of the existing political pyramid.

Meanwhile, our talk of power-sharing with the centre-right Labor government further deters anti-establishment votes.

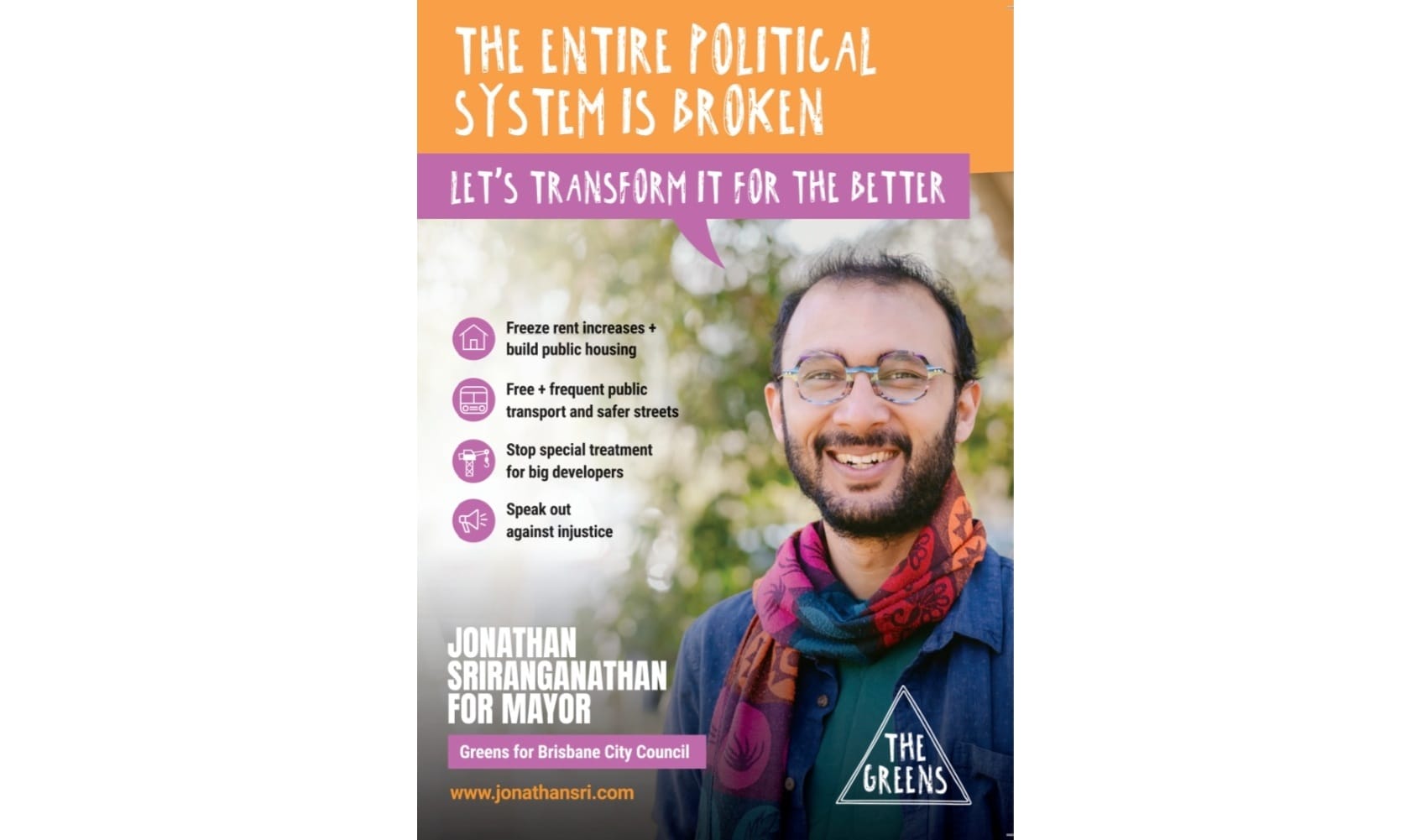

When a politician is more obviously a system outsider (as I was during my seven years as a lone Greens city councillor in Brisbane), consistently voting against right-wing administrations, refusing to make deals behind closed doors, and building grassroots power through community organising, people are more forgiving when you clearly violate establishment norms and conventions. You’re at least behaving consistently with what’s expected of you.

But most voters don’t pay much attention to the details of what political parties say and do. They go off vibes.

And while our opponents were still shrieking about extremism, the Greens were increasingly giving establishment vibes.

When some jaded Greens supporters speak fondly of “returning to the Bob Brown days” I suspect this is what they’re subconsciously reacting to, more-so than a frustration that we’re talking less about koalas and more about banning weapons exports.

I know some active Greens volunteers and staffers would feel differently – they might even resent this claim... But even though the policy platform is far more progressive than Labor's, to superficially-engaged outsiders, the overall Greens party machine in our strongest electorates simply doesn’t look or feel dramatically different from the major parties anymore.

Both during election campaigns and in parliament, big strategic decisions are made by MPs and senior staffers in closed meetings. Just like the major parties, we don't even give ordinary party members a direct vote when choosing a leader – the federal MPs alone make the call, cloistered in secret like a papal conclave.

Pre-election commentary talks of coalition government with Labor. Campaigns are organised primarily via impersonal databases and mass emails, and only secondarily through building meaningful human relationships with empowered, self-motivated supporters.

Meanwhile, key Greens portfolio holders meet in private with government ministers, negotiating to vote for controversial bills without looping in their supporters or the wider public about what’s really going on. In late 2024, when the Greens waived through Labor’s final housing bills without extracting further concessions, this decision was made by federal Greens politicians alone, without any transparent democratic process to include the party’s wider support base.

In that context, footage of Adam behind the DJ decks and Nick McKim playing Fortnite isn’t enough to prove that we’re “doing politics differently.”

To be fair to the Greens, our elected reps do operate less like establishment politicians in some respects. It's more common for Greens MPs to organise public forums about local issues where they're directly accountable to their constituents. Greens elected reps are also more likely to turn down problematic gifts like Qantas Chairman Lounge access (although there are no firm party rules requiring this). And while politicians of all parties run community surveys, Greens reps seem to go to greater efforts to maximise participation rates and make sure they're hearing from as wide a range of demographics as possible.

Max Chandler-Mather's decision to donate a big chunk of his salary to fund his free school breakfast program was a particularly powerful anti-establishment gesture with material benefits for his community, setting a new standard which some other Greens reps have followed.

But speaking as someone who also donated a lot of my six-figure salary during my 7 years as a city councillor, handing over money is relatively easy – handing over structural power is much harder.

And broadly speaking, as the Greens have grown, power has increasingly been concentrated in the hands of MPs and senior staffers, replicating the same major party pattern of disempowering the party's 'rank and file' members, and voters in general.

Both in how they present themselves to the electorate, and how they actually wield power, the Greens are looking and behaving more and more like just another political party.

It's hard to measure this sentiment via exit polls and booth result analysis, but to me at least, it seems probable that by gradually shedding its "doing politics differently" skin, and contesting elections on the major parties' terms, the party also became more vulnerable to the kinds of attacks that were directed against it.

The federal Greens party room inadvertently signalled to voters that they were an establishment party, both wielding and wrestling over structural parliamentary power. They talked about policy changes within individual portfolios, rather than clearly articulating the need for wholesale societal transformation. But if you step into that world of parliamentary deal-making and carefully staged press conferences, you need to consistently re-prosecute the case for deeper system change and explain why it’s impossible to negotiate in good faith with parties who’ve become mere puppets for big business. If you don’t, supporters can easily be turned against you.

The effectiveness of Labor’s attacks that the Greens were “obstructionist” and “playing political games” was of course in part due to the unbalanced platform sizes. A disingenuous narrative spread by the Prime Minister, 90+ federal Labor politicians, and dozens more Labor state MPs and sycophantic media commentators around the country, was inevitably going to cut through more than the counter-narrative from a far smaller group of Greens spokespeople. But the extra sting of the ‘obstructionist’ critique was the suggestion that the Greens were system insiders wielding structural power irresponsibly.

If you show voters that you now hold a degree of structural power – as the Greens essentially did – and after blocking for a while you still end up supporting the government’s agenda, all you really do is piss people off for holding things up. I spoke to multiple upper-middleclass voters at the booths who said things like "I thought you and Labor were in an alliance, but you seem to fight a lot." A key part of their dissatisfaction was not so much that we were standing up to Labor, but that the Greens hadn't met the expectation we'd created that we would cooperate with the establishment.

This is the space where post-election reflections must dig deeper.

If Greens MPs were redistributing power more widely – e.g. through using participatory democracy to guide parliamentary voting decisions– this would perhaps have helped insulate against 'extreme Greens' and 'playing politics' criticisms, because they could more credibly argue that they were representing the will of the wider public. Meaningfully involving supporters in crucial strategic decisions also helps educate our base so that they understand the tensions Greens politicians are facing and can better explain them to friends and family members.

The reality is that we can’t effectively push the major parties to deliver bigger changes unless we’re willing to block government bills in the senate more often. But to publicly justify blocking the government’s agenda, we must first make clear that we exist in opposition to – not as an appendage of – the government and the wider capitalist establishment.

If you’ve routinely pushed a strong case for system change (not just within one policy portfolio area, but for wider cultural and socio-economic transformation), blocking is consistent with your broader stated purpose. But if you signal (intentionally or unintentionally) a desire to become part of the establishment, you’re expected to fall into line to help maintain – not undermine — the status quo.

It’s tricky territory, and anyone who professes to have definitive answers should be treated with scepticism.

None of this should be misconstrued as an argument against the party trying to win more seats in the federal lower house. But we have to be real about what we’re up against.

We have to ensure that in appealing to a diverse electorate (including more centrist and conservative voters), we don't lose sight of why we exist as a party in the first place.

Each election, fewer people vote 1 for the two major parties. And the overall vote share among parties to the left of Labor is consistently trending upwards. But the Greens haven’t capitalised on these trends as much as we could and should have.

Watering down our policy platform even further, self-censoring our criticism of genocide, or attending fewer protest marches won’t move society any closer towards the changes we’re seeking.

The party must find a new path now that’s more overtly and unapologetically anti-establishment, not just in terms of the policies we prioritise and the types of candidates we put forward, but in the effort we put towards talking about and practising systemic change. That means a greater emphasis on political education and mass participatory democracy within our movement, a renewed enthusiasm for grassroots activism tactics that directly challenge government power on the streets, and a willingness to subvert the various parliamentary conventions that constrain and neutralise us.

Whether that’s enough to actually win seats and help change systems remains an open question. Maybe it won’t be.

But if the alternative is that we keep doing what we’ve just done, compromising our message, tactics and identity a little more each election cycle in the vain hope of insulating against increasingly well-coordinated attacks from billionaires and their political puppets, I’d rather try something new.

Thanks for reading! If you appreciate longer, more thoughtful articles like this being available in the public realm, there are three ways you can support this work:

- share this article on social media and/or email or text the link to friends

- make a one-off financial contribution

- sign up for a $1/week monthly subscription to help fund my writing and activism on an ongoing basis

Shout-out to everyone who's been sharing their thoughts with me post-election, and particularly to my partner and number one interlocutor Anna Carlson for her sharp insights (you can hear us chatting more about the election in this Radio Reversal podcast episode)

Member discussion