Peaceful Assembly Act 1992 (QLD): Organising protests without getting fined

Here’s some basic advice on navigating the rules for holding public rallies and marches in Brisbane, which are governed by the Peaceful Assembly Act 1992. This process can also be used for other community events that are seeking to occupy part of a roadway without the prohibitively high costs of hiring a traffic control company.

This is not a detailed guide on how to organise a protest or other public event, but simply a rundown of the specific rules that apply to peaceful assemblies in Brisbane. These rules can sometimes be overridden by special legislation for specific locations and events, such as with the G20 or the Commonwealth Games.

Disclaimer: The following is general advice only. I’m not a lawyer, and this information should not be interpreted as specific legal advice regarding individual situations.

Overview

To put it simply, under Queensland law — specifically the Peaceful Assembly Act 1992 (‘the PAA’) — if you give police and the council written notice of your action/event at least 5 business days before the date of the action, you are allowed to march on and occupy public roads.

If you follow the notice requirements of the PAA so that the action is deemed an ‘authorised assembly,’ you (and anyone participating) will have limited legal immunity from traffic offences or other related offences (e.g. public nuisance) that you might normally be charged with if you stood in the middle of a road.

But note that people can still be charged with other offences (e.g. vandalism, littering, trespass on private property) even if they commit those acts while participating in an authorised assembly.

It’s important to remember that protest actions which directly challenge the power and authority of the state can often be more effective at shifting policy and getting your message across, so you don’t have to go through these legal processes, but then you run a higher risk of arrests and fines.

Some activists argue that every time we organise a protest using the Peaceful Assembly Act process, we are reinforcing and legitimising the power of the state, and so actually we should never formally notify the police. I don’t give that argument a lot of weight, but it’s an ongoing debate in Brisbane’s political organising circles…

Relevance of the Human Rights Act 2019

Importantly, section 22(1) of Queensland’s relatively new Human Rights Act 2019 states that “Every person has the right of peaceful assembly.”

Section 48 of the act states:

“All statutory provisions must, to the extent possible that is consistent with their purpose, be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights.” (sub-section 1)

and

“If a statutory provision can not be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights, the provision must, to the extent possible that is consistent with its purpose, be interpreted in a way that is most compatible with human rights.” (sub-section 2)

This means that when making sense of any ambiguities in the Peaceful Assembly Act, or in interpreting how the act interacts with other city council local laws, the courts have to lean towards whichever interpretations would minimise restrictions on the right to peaceful assembly.

Step 1 – Avoid Date Clashes

Do some basic research online to avoid clashes with other protests and public events. There’s not much point rushing ahead with submitting notices to the police and council if some other important community event is already organised for the time and location you’re considering (unless of course your goal is to disrupt that other event). For spaces like King George Square and Brisbane Square, double-check the BCC website. You can also try calling the council on 3403 8888 but you might not get a straight answer.

The police keep their own calendar of protests they’re aware of. Before you lodge the formal documents, you can try contacting them at MajorEvents.BR@police.qld.gov.au to ask if they’re aware of any potential clashes, but they might be slow in getting back to you, so if you’re in a rush, don’t wait for them.

Step 2 – Lodge a Notice of Intention

Download a copy of a Notice of Intention to Hold a Public Assembly from the Queensland Police website or create your own 'Notice of Intention' (which can even just be an email containing the necessary information).

Fill it out and email it to:

- policelink@police.qld.gov.au

- NOI@brisbane.qld.gov.au (Brisbane City Council)

- MajorEvents.BR@police.qld.gov.au

Advice on filling out the Notice of Intention

The Notice of Intention requirements are defined in section 9 of the Peaceful Assembly Act 1992. Technically, you don’t have to fill out the actual police form, you just have to make sure the written notice has all the information listed in the act. But it’s usually easier to just use the police’s form.

Even though the police form says it must be handwritten, there’s no legal requirement to do this. We always fill out the form by computer and this has never been a problem as long as there’s a signature on it.

Sometimes, Brisbane City Council might ask you to fill out their own Notice of Intention online form, but you’re not legally required to do this. Just email them a copy of the same form that you’ve sent to the police.

Some parts of the form won’t be relevant to your event.

When I’m organising a stationary rally rather than a march, I just write ‘No procession’ in the sections that ask for info about a procession. We don’t usually bother giving much detail about what kind of banners we’re using, because it’s not a legal requirement and the police shouldn’t be preventing you from carrying banners anyway.

You can see an example of a completed notice using the police form at this link. You’ll see that I don’t give any more information than I’m legally required to.

When we’re organising a march, or a larger rally that includes a big stage, we will sometimes also send the police an aerial map showing the layout and march route. This is not a legal requirement, but it calms them down because it reassures them that you’re well organised, and it will mean that they’re less likely to try to make your life difficult.

Deemed approval

Under section 10 of the Peaceful Assembly Act, your protest is ‘taken to be approved’ — that is, approved automatically — if you have emailed in your properly completed Notice of Intention with at least five business days’ notice.

This means that even if council or the police don’t want your protest to go ahead, giving written notice means it’s still legal, and they can’t technically charge you with causing a public nuisance or blocking a roadway etc. (but they can still charge you if you damage property, harm another person etc).

If you’ve given at least five business days’ notice, the only way the council or police can stop you going ahead is if they get a court order from the Magistrates Court preventing the rally.

The actual wording of the act says “if the assembly notice was given not less than 5 business days before the day on which the assembly is held”. In counting the ‘five business days’ my understanding is that you just have to get the notice in before close of business a week beforehand. So if your rally is on a Monday morning, you would have to email your notice before 5pm of the previous Monday (assuming no public holidays).

This interpretation is somewhat open to debate though. For the sake of diplomacy and not giving stressed-out police officers extra motivation to take you to court, it still might be good to get the notice in as early as possible.

Step 3 – Approval/Negotiation with the police

Once police receive your notice of intention, their ordinary process (assuming they have enough staffing capacity) is to give you a call to say hi, and email you out a notice of permission for the public assembly for you to sign. As explained above, if you have given five business days’ written notice, this permission notice is technically not a legal requirement.

However if you lodged your notice with less than five business days’ notice, and the police refuse to give you a notice of permission, your rally won’t be authorised under the Peaceful Assembly Act unless you apply for approval from the courts under section 14.

So if you’re organising your march at short notice, you should try to negotiate with the police to get a notice of permission, otherwise they can charge you with obstructing traffic etc.

My advice is that if you have given your five business days’ notice and don’t technically require the signed notice of permission from the police, you shouldn’t sign it.

The police will often try to include additional conditions attached to their notice of permission, and if you sign the notice, they’ll argue that you’ve agreed to these extra conditions. You could also cross out the conditions you don’t agree to before signing.

How can they stop you?

If you’ve given five business days’ notice, and the police don’t want you to go ahead with the protest (for example, if you’re blocking a very busy road in peak hour), the police must apply for a court order under section 12 of the Peaceful Assembly Act. Before they can apply for a court order, the police (or council) must first hold a mediation session with the protest organisers using an independent mediator in accordance with the processes set out in the Dispute Resolution Centres Act 1990 .

Sometimes police will lie and claim that they’ve already ‘engaged in mediation’ or that ‘mediation has been attempted without successful resolution’ because they’ve had back-and-forth discussions with you via email or face-to-face meetings. But to meet the PAA’s definition of mediation, they actually need to have gone through the proper process with an independent mediator.

So if they try to take you to court, you should always insist on a formal mediation process first.

What this boils down to is that as long as you’ve given adequate notice, the government has to go to a lot of trouble if they want to stop you, and generally it’s easier for them to just agree to the protest and try to impose conditions.

Do I need public liability insurance?

No.

Lately, Brisbane City Council has been telling some organisers that they need insurance to hold a rally in a council park. This is not true. There is no legally enforceable requirement for peaceful assembly organisers to hold insurance, and you should clearly refuse such requests from council or the police.

Legal responsibility for any injuries or damage occurring at a protest is the same for any other use of public space. So for example, if a protestor scratches a parked car, they are personally criminally responsible for. If a protestor twists their ankle in a pothole that council should have repaired, the council might be responsible for medical costs under negligence laws, but if a protestor climbs a tree, falls and hurts themselves, it’s probably their own fault, not the organisers’.

Am I responsible for traffic control or traffic management plans?

No.

Police or the council might occasionally tell you that you also need to apply for a road closure permit or organise traffic control to shut off streets and divert traffic. This isn't actually true. The whole point of the Peaceful Assembly Act is to allow residents who don't have the money to hire a traffic control company to be able to use the street for the purposes of public assembly. If traffic control is considered necessary to allow residents to peacefully assemble on a particular street, it's technically up to council or the police to provide this.

Can they prevent me from erecting shade shelters and info tables as part of a rally?

The legal situation is unclear, but probably not.

Setting up temporary shade shelters/gazebos is part of a peaceful assembly, and as long as they’re properly secured against the wind and you’re not going over the top with them, you should be fine.

In places like King George Square, the council might try to insist on a condition preventing shade gazebos, but I doubt it would be legally enforceable.

Section 5 of the Peaceful Assembly Act says the right to peaceful assembly is subject “only to such restrictions as are necessary and reasonable in a democratic society in the interests of public safety, or public order” etc. On a hot sunny day, denying protestors access to shade is an unreasonable restriction on free assembly, so if you hold your ground when negotiating with police and council, they will not legally be able to insist on banning gazebos.

How much noise can we make?

There are no specific rules on noise limits and volumes within the Peaceful Assembly Act, but the act allows for restrictions that are necessary to protect the health, safety, rights and freedoms of other people. It’s probably arguable that the general state and federal environmental protection laws against noise pollution would apply, but as far as I know, it’s never been an issue at a rally.

In some publicly accessible spaces — such as inside the lobby of the State Government HQ at 1 William St — building security might ask you not to use a PA system/megaphones, but if you've lodged a notice of intention, they can't stop you. If you haven't lodged a notice of intention, it'll come down to a test of wills between you and the police/security. A police sergeant would have to be pretty stupid/crazy to start arresting or fining protesters simply on the basis that their PA is too loud.

In the past, we’ve had loud bands and DJs playing at events that were authorised under the Peaceful Assembly Act, and haven’t had any problems. I think the best approach is to use commonsense and don’t turn up the speakers so loud that you deafen your own supporters.

You should think practically about which direction your speakers are pointed to maximise coverage of the crowd. It helps to lift speakers off the ground with stands or milk crates. For larger rallies, it’s not ideal to rely on a single speaker pointed in one direction, as that’ll mean that when someone is standing right in front of the speakers it's way too loud, while someone standing a bit off to the side still can't really hear the speeches properly.

Where can we legally assemble?

The Peaceful Assembly Act protects the right to protest in any public place. A public place is defined in section 4 as including:

“(a) a road; and

(b) a place open to or used by the public as of right; and

(c) a place for the time being open to or used by the public, whether or not—

(i) the place is ordinarily open to or used by the public; or

(ii) by the express or implied consent of the owner or occupier; or (iii) on payment of money;”

As you can see, this broad definition appears to include publicly accessible spaces on private land, such as in the forecourt or lobby of a big office tower, or inside a shopping mall (of course, if security guards on a private property know you’re coming, they’ll probably lock you out). However the PAA doesn’t provide immunity from the common law offense of trespass, so even if the private space is publicly accessible, if the property owners can convince the police that you’re trespassing, they might still arrest you. This is a bit of a legal grey area.

Importantly, the broad defintion above arguably also applies to land controlled by South Bank Corporation.

In recent years, South Bank has strongly resisted any protests taking place within the parklands on the basis that South Bank is “a family-friendly place” (I find this amusing because it implies that other parks like Roma Street are not family-friendly). But in fact, in terms of how the Peaceful Assembly Act operates, South Bank Parklands is just like any other park, so if you send your Notice of Intention to both the police and council with five business days’ notice, they would need a court order to stop you.

It’s pretty straightforward

So that’s basically all you need to know to get started.

Although for the last forty or fifty years, Australian streets have been seen as the exclusive domain of cars, there’s no reason we shouldn’t reclaim them as public spaces for people too.

If you lodge a Notice of Intention at least one week before the protest, you can legally block roads, hold protest gigs in public parks, and arguably even hold protest pool parties down at South Bank.

I find it’s generally better to maintain open channels of communication with the police, because they are more likely to panic and do something stupid if you take them by surprise. But remember: you have a democratic right to peaceful assembly, so don’t let them insist on conditions that unreasonably restrict or limit that right.

Political context matters

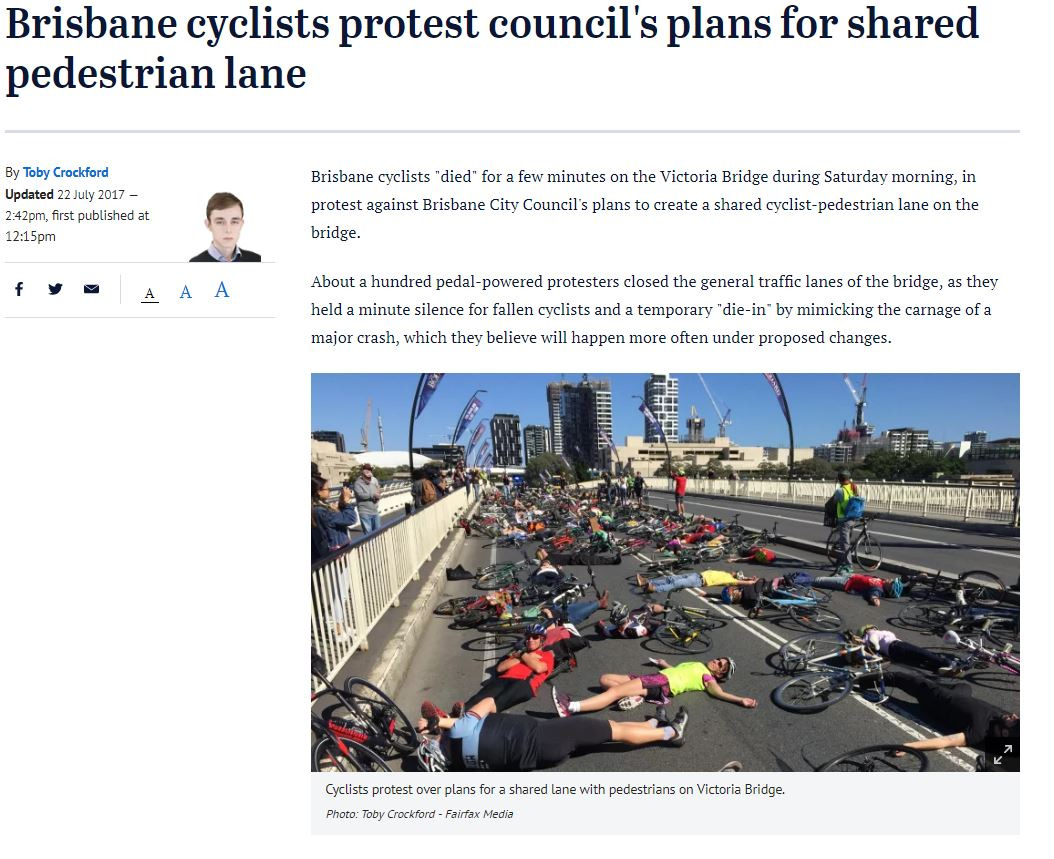

The extent to which police try to push back on planned protests — i.e. by applying to the Magistrates Court for an order prohibiting a street march — depends heavily on the broader political context and on public commentary about the legitimacy of blocking roads, the specific issues in question, and the motivations of the protest organisers.

There have been times over the past few years, such as during covid lockdowns, or regarding the 2019 Extinction Rebellion/climate justice protests, when police have been much less reasonable and flexible about negotiating and supporting authorised assemblies on large and busy road corridors, and gone to greater lengths to get march routes changed or to prevent protests altogether via court orders.

Importantly, the Queensland Police Service is a political entity that’s highly sensitive to public opinion. If the senior commanders are worried that police are getting a bad reputation for being too heavy-handed about suppressing protests, they might be less likely to take you to court, whereas if there’s a general climate of public frustration at protesters regularly blocking roads, the cops might be less tolerant of assemblies that disrupt traffic.

It's hard to provide general advice on whether you should or shouldn't lodge a notice for a given event (or if it’s better to take the police by surprise) because the outcome depends on the subjective discretion and biases of individual police commanders and judges. Importantly, it's still possible to win in court even if the police apply to a magistrate for an order preventing your assembly.

At the end of the day, the best way for us to defend our right to assemble in public places is to exercise it on a regular basis and normalise the idea that roads and squares can and should be used for large rallies and protests.

Whether you’re organising a small street party that blocks a minor intersection in West End, or a major rally through the CBD at peak hour, the Peaceful Assembly Act protects your right to occupy public spaces without fined for traffic offences, and without having to spend a lot of money on traffic control.

Ok thanks for reading! Hopefully all this is helpful. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber if you value resources like this being freely available to the public.

I also recommend checking out resources produced by the excellent Queensland-based collective Action Ready. If you’re an activist planning an action who wants some more specific advice, you’re welcome to flick me an email via office@jonathansri.com (no promises that I’ll reply at short notice though). If you’re organising a protest and the police are pushing back, reaching out to elected Queensland Greens politicians is also a good idea.

Member discussion