To Fight Back Against Unsustainable Developments like the Queens Wharf Mega-Casino, We Must Occupy

Brisbanites are having our city sold out from under us, and we need to fight back. On Saturday, April 22, I’ll be attending and supporting a rally and 24-hour creative occupation hosted by Right to the City to protest the construction of the Queen’s Wharf mega-casino, and the theft of public land committed by the Queensland government. But the occupation isn’t just a protest against the casino. It’s about pushing back against the negative impacts of gentrification, against unsustainable development throughout Brisbane, and against the fact that every square centimetre of our city now has a price tag on it.

Public spaces - especially inner-city parks - are incredibly valuable to the communities that own them. They are not owned and controlled by corporate entities who have the power to evict or exclude people from these premises at will. They offer people an alternative to (and a refuge from) commercialised spaces where active consumption is a precondition to feeling welcome. They provide spaces for people to meet, share ideas, and engage in collective artistic, sporting, and political projects without incurring a cost.

Many Brisbanites still don’t realise that the casino developers are proposing to turn the middle segment of Queens Park (one of the few open green spaces in the CBD) into an entrance walkway for an underground shopping mall. In total, the State Government’s support for the mega-casino would see over 13 hectares of public land given over to private developers. The developers claim much of this land will be open to the public after the casino is built. But what they really mean is that it will be accessible to those members of the public whose presence is profitable: those who will consume at their high-end shops, those who will drink at their posh bars, and those who will gamble at their tables and poker machines. There will be no affordable housing or educational facilities delivered as part of this project. Even the footbridge to South Bank makes no sense from a transport planning perspective, and was proposed to connect directly to the gaming room floor of the casino.

I’ve visited over-crowded cities where you can walk a dozen streets and not find a single place to stop and rest unless you’re buying or consuming something. I don’t want Brisbane to become one of those cities. The Queensland government is handing over publicly owned land to the casino developers, but we’ve been denied any opportunity for informed input or control. The only form of ‘consultation’ was a poorly publicised four-week window for submissions back in 2015 that no-one heard about (though even if we had heard about it and made submissions, our recent experiences of other major development projects around Brissie make it pretty obvious that we would’ve been ignored).

Predictably, the government’s response to dissent is to emphasise how many wealthy international tourists the project will attract, and how many temporary construction jobs it will create. The many negative social impacts of a major casino resort (and the resultant negative economic impacts) are left off the balance sheet. Over the past four decades, every major Australian casino project has started out by claiming it will target international high rollers, but inevitably ends up shifting its business model to depend almost entirely on local gamblers who lose more than they can afford. Casinos are a net drain on the economy and a blight on society, which makes it all the more outrageous that in this case, the government has given the developers valuable inner-city riverfront land for far less than market value.

This weekend’s creative occupation is an opportunity to make demands for how this public land could be put to better use.

Creative occupations offer a more strategically effective alternative to conventional rally-and-march protests, which are increasingly understood by many activists as protests-by-template. The process for gaining approval for these protests is now just as formalised and bureaucratised as applying for a driver’s license. Just as the state grants you permission to drive a vehicle, so too does the state grant you permission to assemble in public and express your dissatisfaction with the state’s actions.

While they can still serve a range of useful purposes, Saturday morning rally-and-march template protests have (generally speaking) become mundane and routine. They do not disrupt the ‘everyday’ and so are less likely to challenge social norms and the political status quo. In an era where the big decisions that shape our city are increasingly made by multinational corporations rather than elected officials, temporary non-disruptive protests are too easy for the political establishment to ignore. They no longer represent any meaningful challenge to state power or corporate hegemony, and can even serve to legitimise and entrench the status quo by creating the illusion of a free society that allows democratic dissent, even though such expressions of dissent are carefully controlled and can only occur within narrowly defined parameters.

It’s increasingly common for governments to deny permission for any protest that departs from the standard template, usually on the spurious grounds of ‘protecting public safety’ or impacts to big business profits. Occupations are a direct means of pushing back against government control by asserting the necessity of public space, and the right of ordinary people to use it for any purpose they wish. Occupations can perhaps be understood as a form of alter-politics rather than raw ‘anti-politics’, as they provide a physical space in which to practice what we preach. At a creative occupation, we aren’t just calling for a better world - we’re living it.

By disrupting the everyday, business-as-usual operation of city spaces, occupations create a space for positive demonstrations of alternatives to current political ways of thinking, rather than simple, adversarial opposition. They allow participants to define and contribute to a political practice that reflects the world the protesters wish to create. They become hubs for the exchange of ideas and the forging of new connections. Assembling together in public spaces for longer than a fleeting rally and march gives activists the time to engage in nuanced discussions about strategy and tactics, and about what kind of utopia we are fighting for.

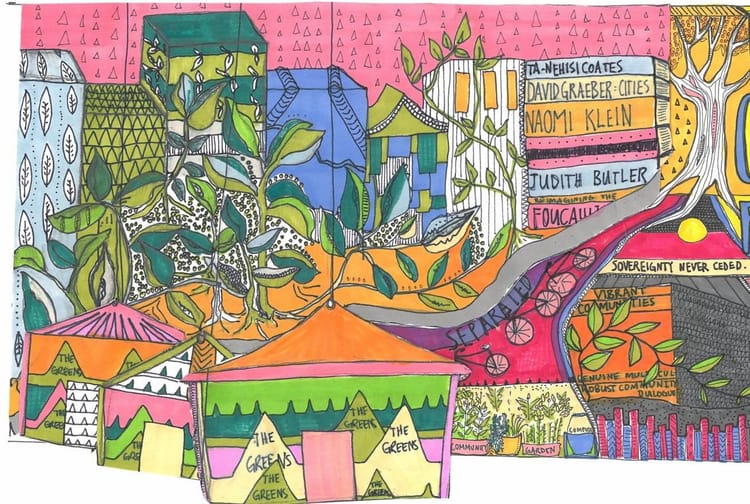

Perhaps most importantly, occupations are supposed to be fun. Musicians are encouraged to bring instruments. Artists are encouraged to display their work. The days and evenings are filled with workshops, public lectures and discussion groups, community banquets, poetry readings, parties and gigs. People will be staying overnight, in direct challenge to council and government regulations which criminalise homelessness. We will be pushing back against the forces of corporate capitalism, not with a mundane template protest that is quickly forgotten, but with a joyful, creative, engaging occupation that demonstrates our willingness to hold space and engage in longer, more disruptive civil disobedience if such mega-developments continue to receive approval.

Campaigns against unsustainable and socially unjust mega-developments require a range of tactics to succeed. But community movements against projects like the East-West link down in Melbourne remind us that success is possible, even when governments and developers act like the project is already a finalised done deal.

We must fight back.

Member discussion