Cul de sac politics: Have the Australian Greens hit a strategic dead-end?

Over the past 24 months, crucial sliding doors moments in Greens politics have left the party looking less and less politically relevant. One Nation is on the rise, capturing widespread disillusionment with the major parties, while federally the Greens are stagnating.

In his article for Deepcut News this week, former MP for Griffith, Max Chandler-Mather, rightly argues that the Greens need to pivot towards a more robust critique of the political establishment that taps into widespread frustration with the two major parties.

He's been saying this for a while now, and he's not the only one. So why hasn't it happened?

Answering that requires an understanding of the party's recent history, and the pressure towards status quo politics embodied in their remaining lower house seat of Ryan, held by Elizabeth Watson-Brown...

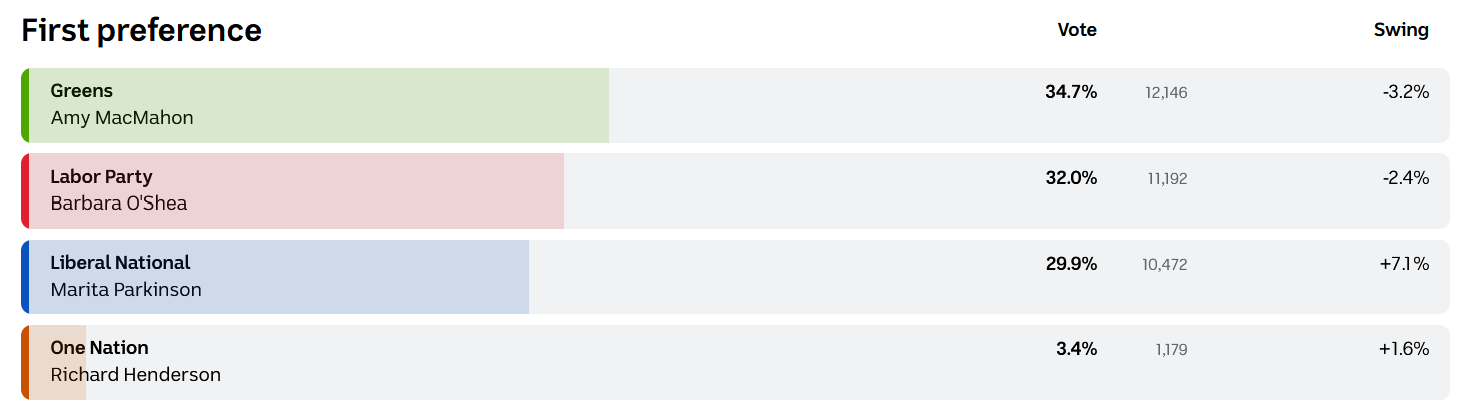

Looking back, the Greens losing the state seat of South Brisbane in the 2024 Queensland election (immediately after multiple seat losses in the ACT election) stands out as a significant turning point for the party. That's primarily because a lot of people drew woefully incorrect conclusions from the results.

Up until 2020, South Brisbane (which sits within the federal electorate of Griffith) had been Labor-held for 94 years out of the past 100. There were specific reasons why Labor regained this seat from the Greens in 2024, most notably that in the primary vote count, the LNP remained in third place despite their statewide surge, and their preferences mostly flowed to Labor.

I think my initial analysis of why the Greens didn’t do better in that state election – especially the party’s failure to respond effectively to the LNP’s youth crime messaging – turned out be largely correct, but there were also several additional local factors specific to South Brisbane.

Australian Greens leadership – particularly politicians and senior staffers in other states – apparently didn’t make time to properly understand the South Brisbane loss. Instead, it seems to have been misinterpreted as evidence that the general approach taken by Max Chandler-Mather was electorally damaging (this is despite the fact that earlier in the same year, we achieved a record-high primary vote in Brisbane's council election when I ran for mayor).

Max had spent several years building party support for a broader social democracy campaign platform which appealed to those who feel abandoned by the political establishment, simultaneously neutralising a major barrier that swing voters commonly reported – that the party only cared about environmental issues. While I haven’t always agreed 100% with his approach (either on policy priorities or on how elected Greens reps should wield power), I think he deserves a large share of the credit for the Greens winning three more House of Representatives seats and a second Queensland senate seat in 2022.

Crucially, Max was also a strong advocate against the Greens placidly rolling over and rubber-stamping Labor bills. He seems to have convinced the Greens party room to support a more robust negotiating posture on some issues – particularly housing.

But after the 2024 state election loss of South Brisbane, Greens power-holders outside Queensland concluded that Max’s approach – both in terms of parliamentary strategy, and broader campaign messaging – wasn’t a winning electoral formula after all. For them, the South Brisbane loss essentially delegitimised the shift that Max and others had been advocating for.

So between late 2024 and early 2025, the federal party room shifted messaging and emphasis significantly, and hurriedly passed several problematic Labor bills that effectively propped up the political status quo. To a casual observer, the overall impression the Greens conveyed was "we don't want to make big, drastic changes."

Thus, in the 2025 federal election campaign, the Greens didn’t push as strongly on housing affordability. Having picked a big fight over it in the preceding three years, they failed to centre it in their election campaign, and didn't lock in the votes of larger housing-stressed constituencies. Instead, they spoke of ‘working closely’ and ‘sharing power’ with Labor, and ran on a minimally-controversial reformist platform, mostly using orthodox campaign tactics that weren’t radically different from the major parties’ approaches.

It didn’t work.

In fact, by adopting national messaging that diverged so markedly from Max's angle over the preceding three years, the party undermined its Brisbane campaigns in particular. After the Greens rolled over and passed Labor's piss-weak housing bills, frustrated renters in key seats weren't offered a strong enough reason to prioritise the Greens ahead of Labor. Having argued vociferously against the treatment of housing as a for-profit commodity, the party now finds itself in the odd position where its only remaining House of Representatives MP is apparently a property investor.

But rather than being recognised as evidence that small-target, system insider-style politics isn’t a winning formula for the Greens, the party’s lacklustre federal result – and particularly the losses of Griffith, Brisbane and Melbourne – seems to have been misinterpreted as further proof that standing up strongly to the political establishment and the neoliberal consensus doesn’t win enough votes.

Since May 2025, the party hasn’t proposed anything new or spicy enough to attract widespread media or public attention, or effectively used its balance of power in the Senate to secure significant tangible wins (Osman Faruqi’s insightful commentary on how the Greens handled Labor’s Environmental Protection Reform bill is worth listening to for an example of this). Meanwhile, the Greens sycophantically 'welcomed' the social cohesion royal commission that the Zionist lobby has been pushing for, even though it's based on fundamentally flawed premises and revolves around an absurdly broad definition of antisemitism that essentially purports to treat criticism of Israel as de facto racist.

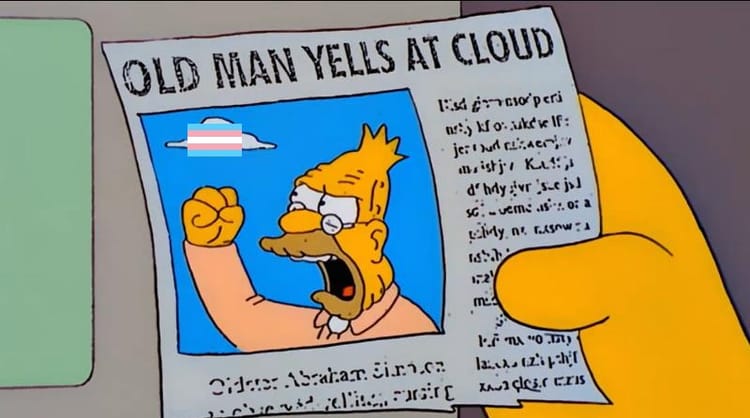

Reading through the Saturday Paper's recent interview with Larissa Waters, I can't help but feel underwhelmed. The opening paragraph suggests that the Greens are "positioning themselves as the party of progressive reform and stability."

Not 'pushing for big changes' or 'shaking up unjust systems' – reform and stability. This seems a stark contrast from the UK Greens, who are taking an unashamedly anti-establishment posture under new leader Zack Polanski, which voters are responding positively to.

In the Saturday Paper article, Larissa does talk of Australia needing to 'change direction,' and offers a modest critique of the political establishment...

“That’s because they’re both status quo parties, and they’re both accepting political donations from the same big companies, often the big polluters, and they’re both not wanting to actually change the system, because the system is working quite nicely for them and the people that donate to them, namely the big corporations and the very wealthy."

But she then dilutes this already-moderate message with comments about working with the government, scrutinising draft regulations and negotiating politely to achieve minor reforms – classic status quo politician talk.

Larissa has struck a similar tone in other recent interviews (e.g. her 29 January podcast interview with Natarsha Belling). Her talk of 'policy reform,' her complaints about the lack of respect in parliamentary debate, and her calm, measured delivery undoubtedly appeal to middle-class centrists who value civility and continuity, but not enough to peel them off from supporting Labor. And even though she rightly mentions pain points like housing costs and grocery bills, her word choice and overall approach don't go anywhere near far enough in reflecting the rage and desperation that so many people are feeling right now.

A statesmanslike, system-insider image does win over a few centrist voters, but it doesn't help build a mandate for the Greens to push hard for bolder action on issues like climate change and housing justice, and it evidently doesn't appeal to larger numbers of swing voters who are frustrated with the status quo.

The party was always going to take time to rebuild momentum after losing 3 out of 4 lower house MPs, including its party leader. But it’s now over eight months since the federal election, and despite holding balance of power in the Senate, the Greens have had relatively little cut-through or influence over the national political agenda.

Reversing out of the Ryan cul de sac?

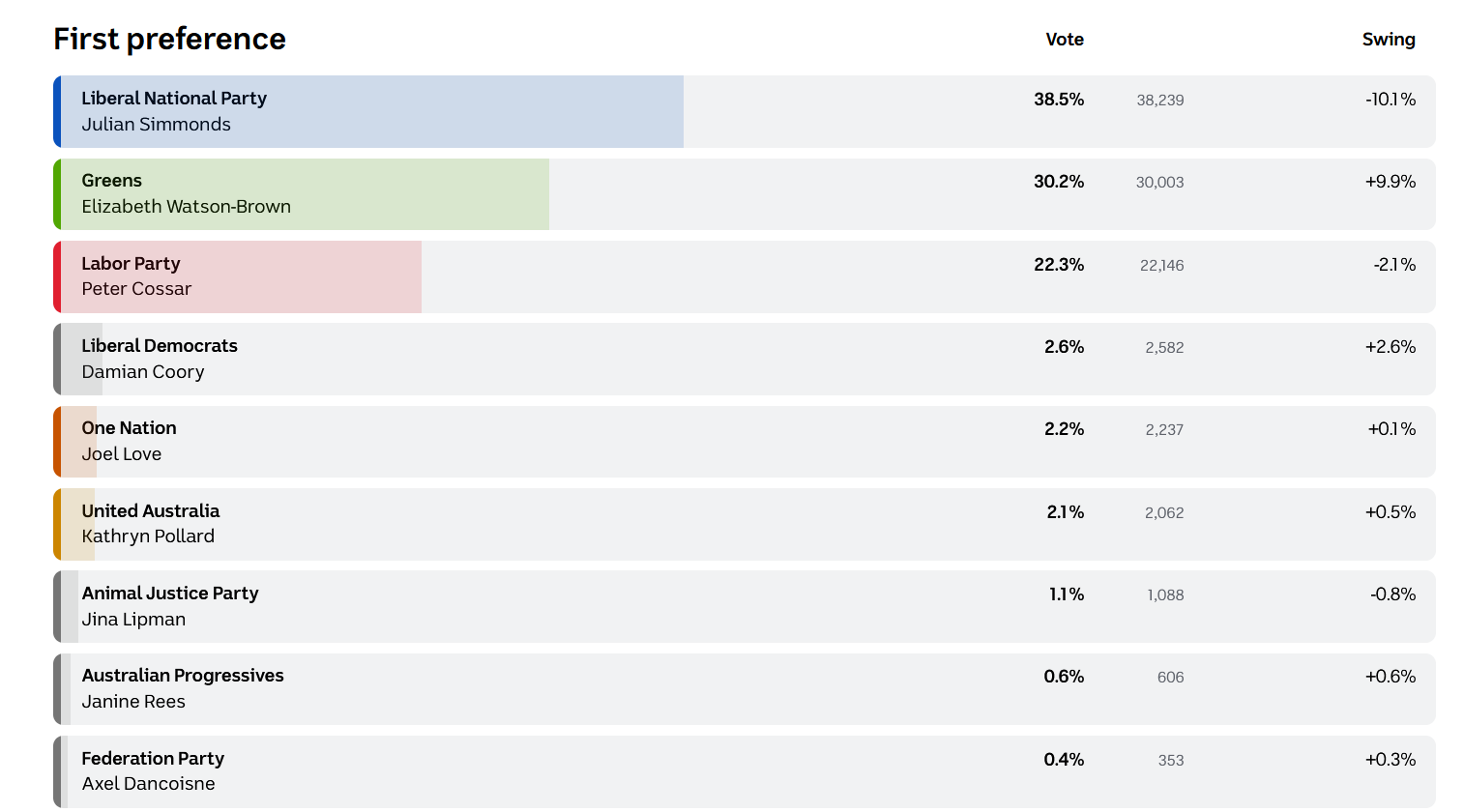

One of the bigger but less obvious factors that I suspect is preventing the Greens from pivoting firmly towards a "we stand for system change" narrative is the demography of the party’s one remaining federal lower house seat – Ryan.

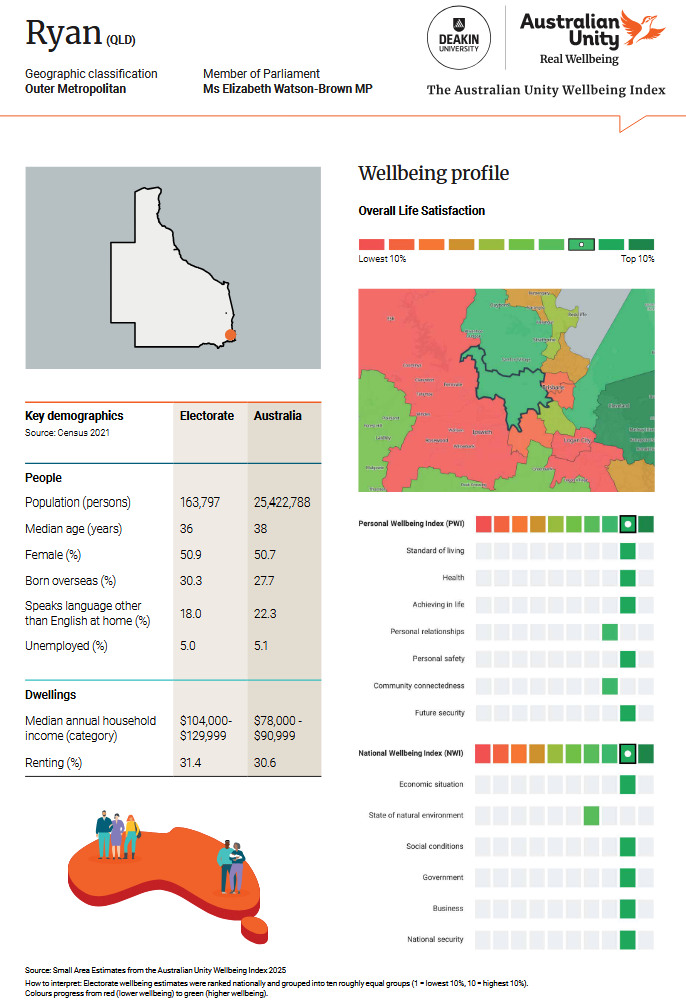

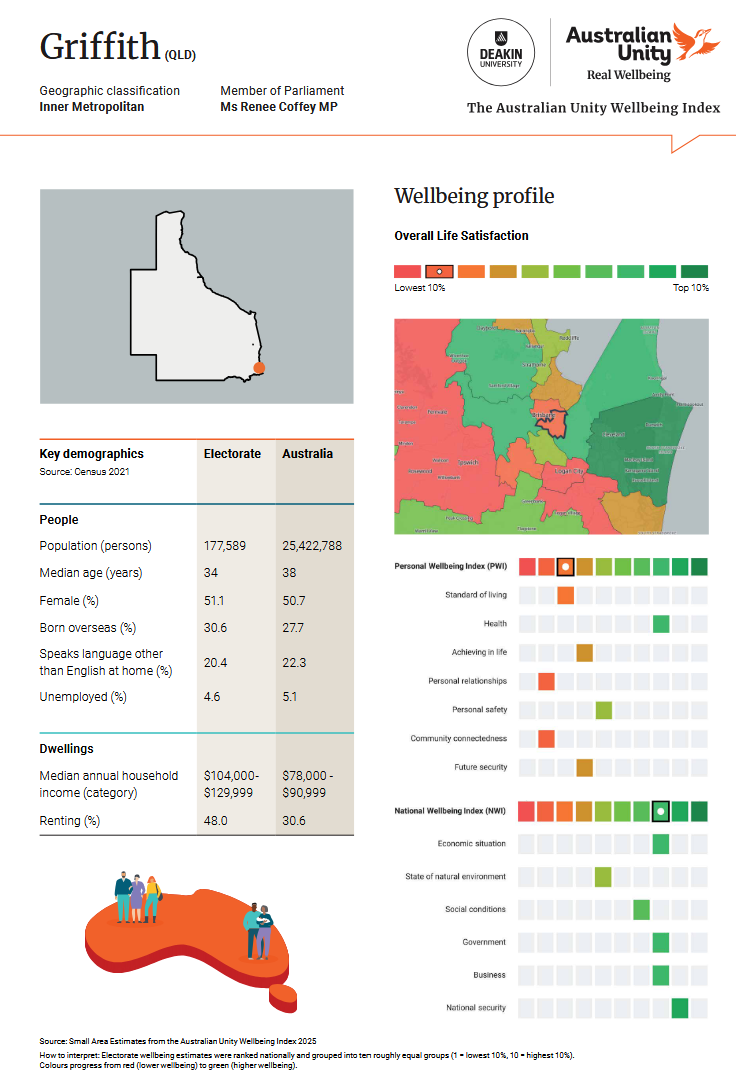

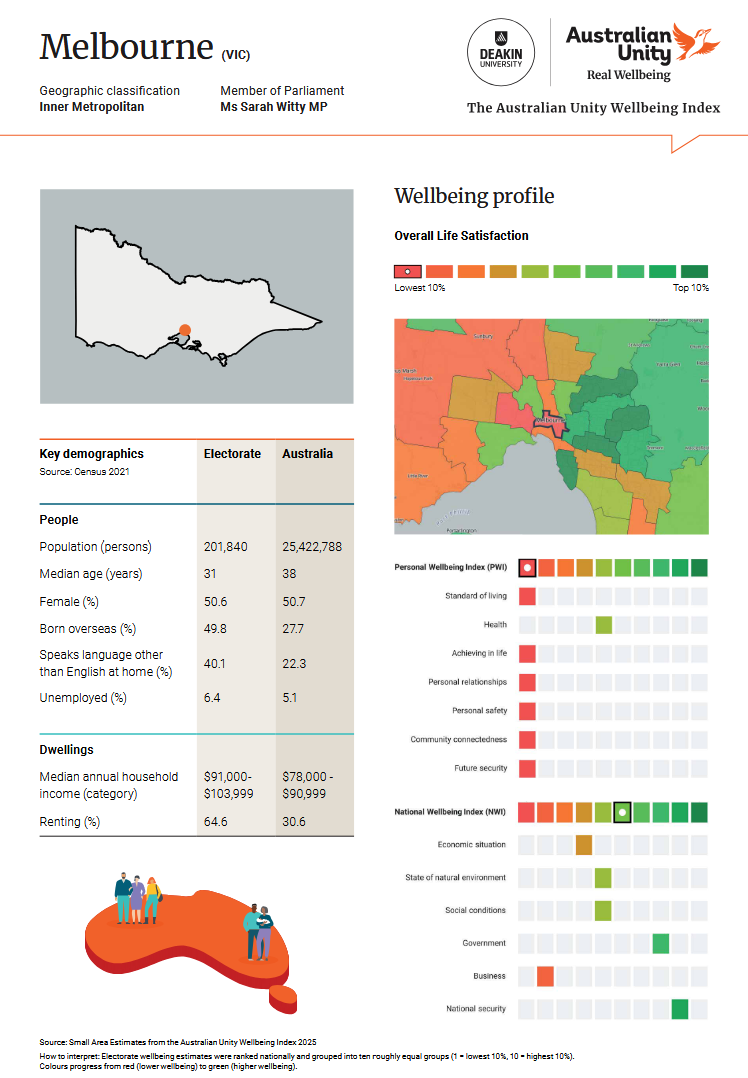

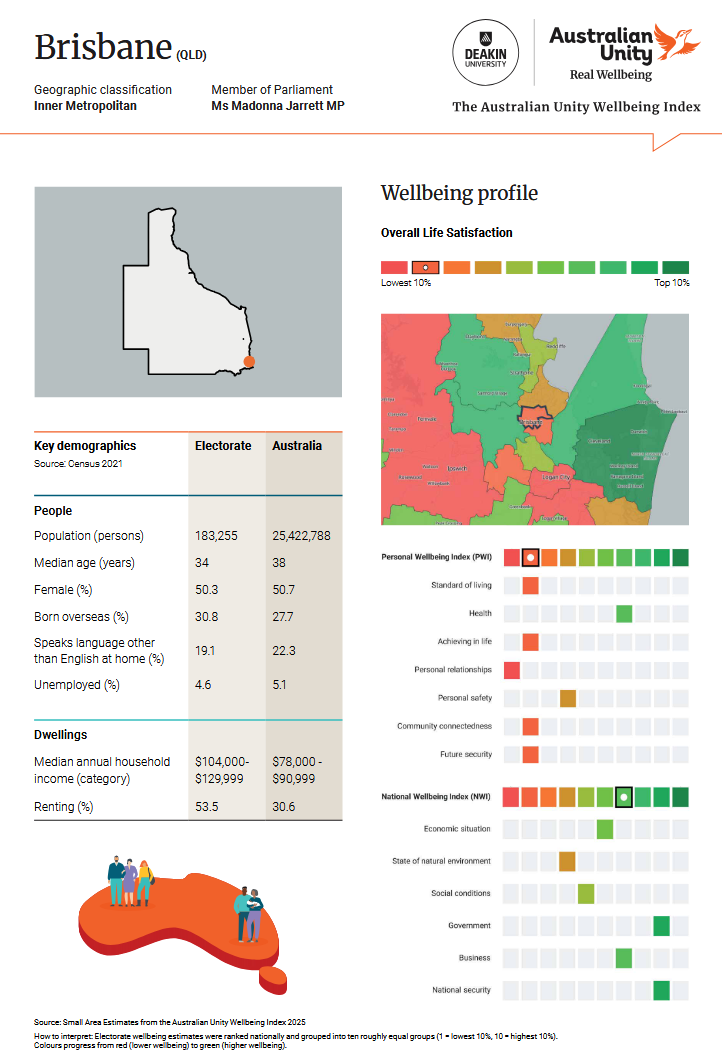

Elizabeth Watson-Brown's Ryan electorate is, on average, much more conservative than Brisbane, Griffith, Melbourne or any of the other key seats the Greens might hope to win in coming elections.

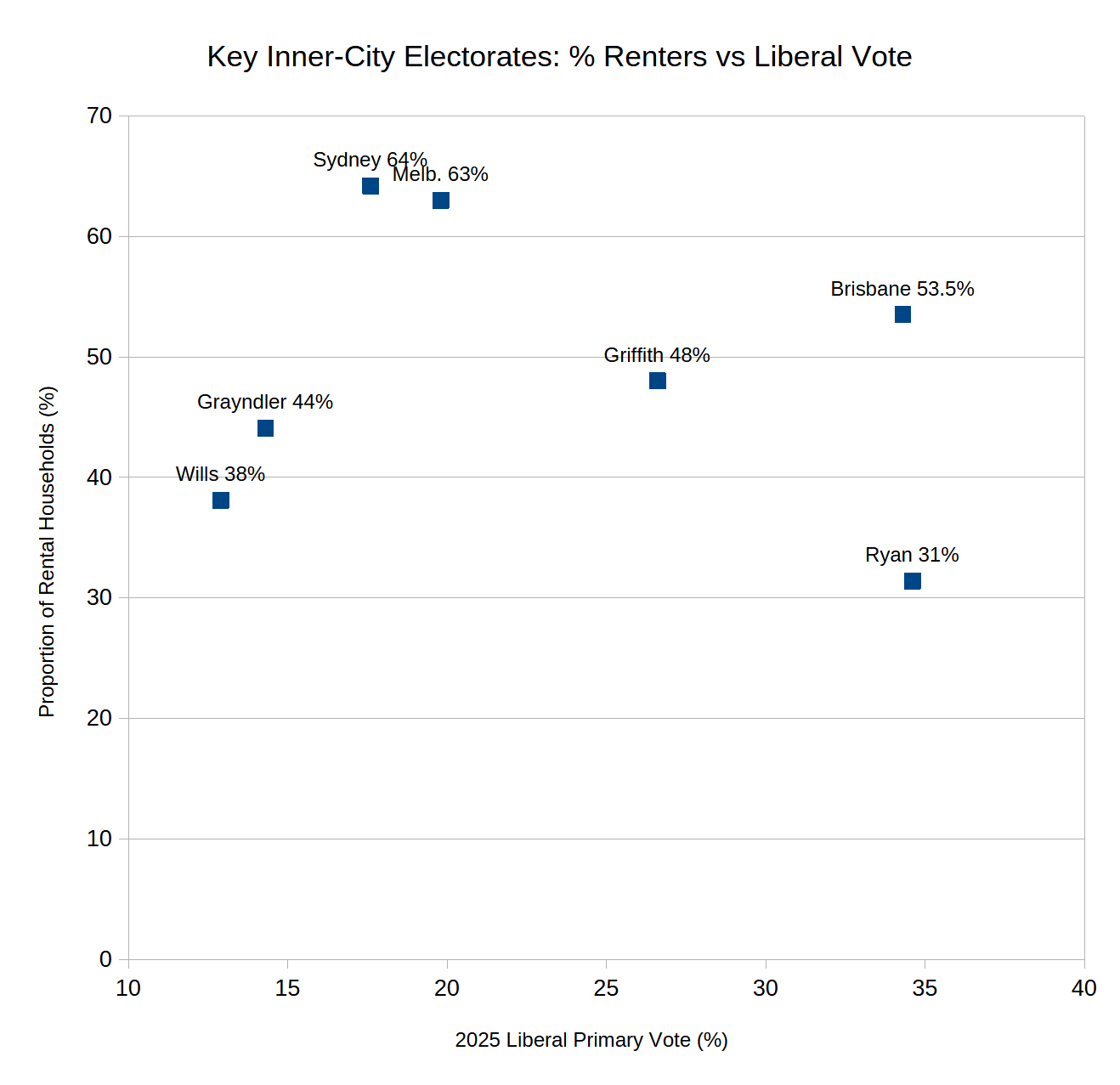

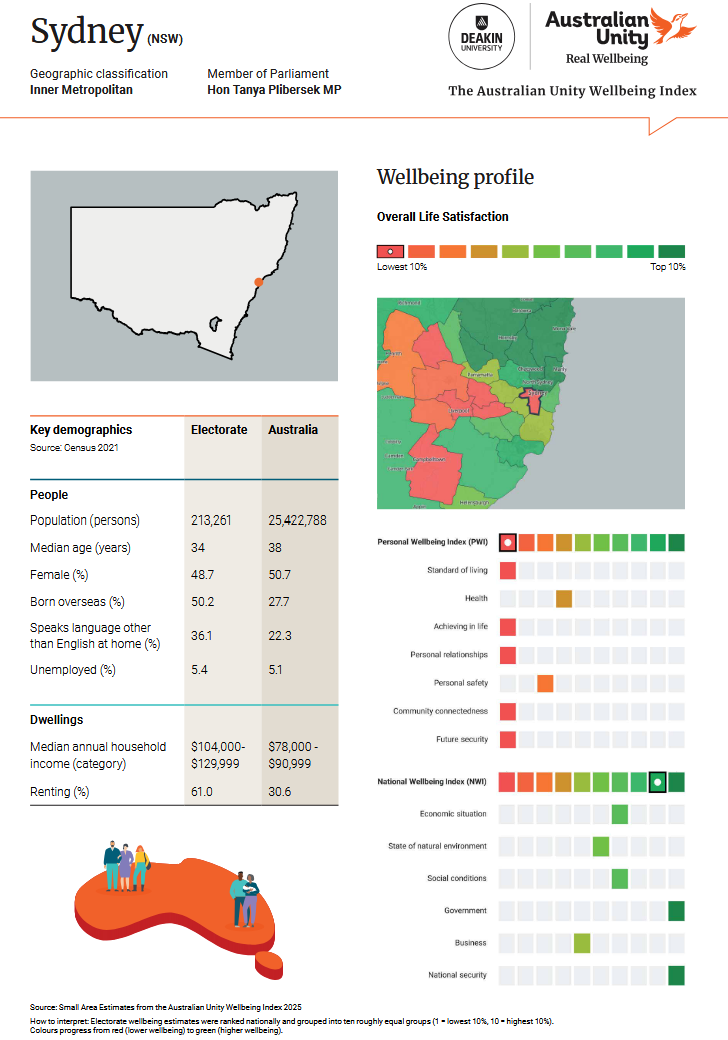

Take a look at this graph, which shows the proportion of rental households in key east-coast inner-city electorates, compared to the Liberal primary vote in the 2025 election.

Electorates like Sydney and Melbourne are home to twice as many renters as Ryan. And the Liberal primary vote in those seats is under 20%, or in the case of Wills, as low as 12.9%.

Ryan is home to many more swinging Liberal voters and significantly fewer renters than any of the other seats where Greens support and campaigning capacity is strongest.

To win and retain Ryan, the Greens had to appeal to thousands of centrist Liberal voters who own their own homes. This demographic has never mattered as much in electorates like Melbourne or Wills, and won't be particularly important when Tanya Plibersek retires and the Greens go after Sydney more strongly.

The demographic differences between Ryan and those other inner-city electorates, or indeed suburban electorates such as Moreton and Fraser (where the Greens saw promising positive swings in the 2025 election) become starker when you compare variables like net wealth, mortgage stress or cultural diversity.

And the divergences are even more pronounced when you look at voters' subjective sentiment about how they're going in life.

The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index explores people's own perceptions of their standard of living, health, future security etc. in each federal electorate. Whereas Ryan voters rank very high in overall life satisfaction and in the report's 'Personal Wellbeing Index,' voters in Griffith, Brisbane, Melbourne, Wills, Fraser and indeed many of the Greens' strongest federal seats, rank far lower.

Unlike all those other seats, culturally Ryan seems to have more in common with teal-held electorates like Kooyong, MacKellar, and Wentworth, which all also report very high personal wellbeing and life satisfaction.

This highlights a deeper tension the Greens aren't properly grappling with.

For electorates like Ryan, the underlying story the Greens lean towards to win people over revolves around stability and responsible governance. The majority of Ryan voters feel they have it pretty good, don't really see the need for deep, drastic change, and may not (yet) even accept the premise that the entire political system is irredeemably stacked in favour of big corporations.

This is perhaps partly why Greens strategists in Ryan argued strongly for a 'Keep Dutton out' message in the 2025 election campaign. Dutton had been framed as the change candidate – a Trump style disruptor. And most Ryan voters didn't want disruptive change.

Even where the Greens were proposing progressive reforms like free university, they were often pitched as a return to past policies from the good old days, rather than something entirely new.

I don’t want to oversell the contrast between Ryan and other metropolitan seats, and I'm not suggesting the Greens have to make a binary choice between retaining Ryan and winning other electorates.

But they do have to make a clear choice as to whether they're an anti-establishment party of deep change, or progressive reformists who might shift a few couches around but aren't going to replace the broken furniture.

If the party’s election campaign strategy and messaging revolve too heavily around defending the Ryan electorate, ruling out insurgent tactics or bold policy announcements that might turn off middle-class swing voters in Brisbane’s affluent western suburbs, it will be poorly positioned to regain inner-city seats like Melbourne or Griffith. And it certainly won’t be able to win over the outer-suburban migrant and working-class voters who are seeking alternatives to the major parties, and who represent the Greens’ best opportunity to grow beyond the party’s inner-city base.

I think on some level, leaders like Larissa are aware of this tension. But for now, their response is seemingly to place a bet each way. They're caught between appealing to well-off voters in electorates like Ryan, who mostly don't want big changes, while also wanting to connect with millions around the country who are struggling with rising rents and falling living standards, and who definitely do want significant change.

In practice, decisions about what balance to strike and what strategy to pursue will be heavily shaped by senior electorate office staffers, as well as the federal Greens politicians themselves. Whether consciously or unconsciously, many of these key power-holders will prefer whichever pathway maximises their own job security and makes their work easier. This will likely lead to a heavy decision-making bias towards whatever is deemed necessary to retain Ryan.

There are of course plenty of Greens politicians who to varying degrees self-consciously choose not to settle for a comfortable, small-target strategy. But the party’s overall image and political posture essentially remains one of centre-left incremental reformism.

Rather than trying to offer one package to upper-middle-class voters in electorates like Ryan, and a very different package to the rest of the country, the Greens will have to do the harder work of convincing Ryan voters to get on board with a program of radical transformation. Adopting a more conservative approach to sandbag Ryan is a dead-end strategy.

If the Greens want to rebuild momentum and offer disillusioned voters an inspiring alternative to One Nation, the party needs to style itself unambiguously as a party of change, rather than looking – to the average disengaged voter – as though it's uncritically supporting Labor and maintaining the status quo.

For more articles like this, please consider subscribing to support my work...

For a deeper dive into an alternative strategic orientation that I think the Greens should consider adopting, have a read of this two-part article I wrote after the 2024 state election.

Member discussion