Koalas are trying to return to Greenslopes and Annerley – but they’ll need our help

The older bloke walking the wannabe-horse sees us staring up at the tree canopy and smiles.

"You won't find any koalas around here," he tells me confidently (perhaps a tad patronisingly).

"Oh really? Do you walk this way often?" I reply.

"Yep... Lived here thirty years. There's no koalas on this side of Nursery Road, but I sometimes see them down in Mansfield where I work."

"But we saw one in that tree there just last week."

He clearly doesn't believe us... Squints at me like I might be a little stupid, or I'm trying to con him somehow.

I pull out my phone to show him the photos and video.

His eyes widen. He looks back and forth from the images to the tree I'm talking about, like he's seeing his neighbourhood in a completely new light. His massive dog is getting impatient though, so he smiles and hurries off (without really conceding that he was wrong). But as the hound pulls him along, I notice him scanning the tree canopy above the footpath, maybe for the first time in years.

The brief interaction reminds me that most people have very little idea about what kinds of creatures are moving through their backyards and local parks after dark, or what might be watching them from the trees that grow alongside their regular walking route.

In a world of seemingly endless environmental destruction, I look for glimmers of hope wherever I can. It turns out there are a few right here on Brisbane's south side...

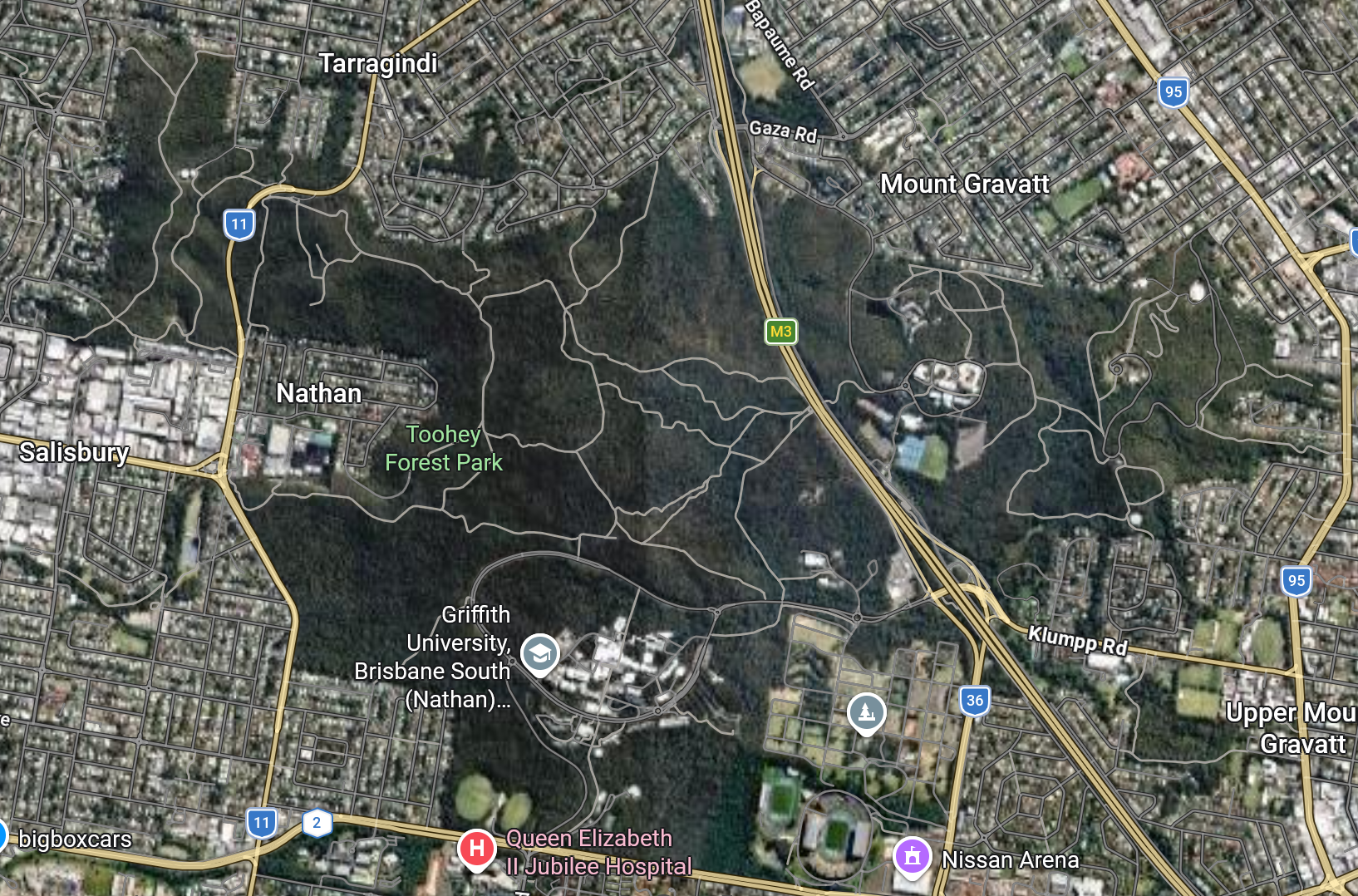

In the 1980s, koalas were considered locally extinct in Toohey Forest and Mount Gravatt Outlook Reserve.

Up until the late 1920s, the Queensland government actively encouraged hunting of koalas for their furs, with over 600 000 koala pelts (yes, you read that number correctly) collected and sold in August 1927 alone. Between the intentional hunting of literally millions of Queensland koalas, and decades of widespread tree-clearing as the city sprawled outwards, it's not surprising Brisbane ecologists couldn't find them in this patch of remnant urban bushland, entirely surrounded by housing and industrial development.

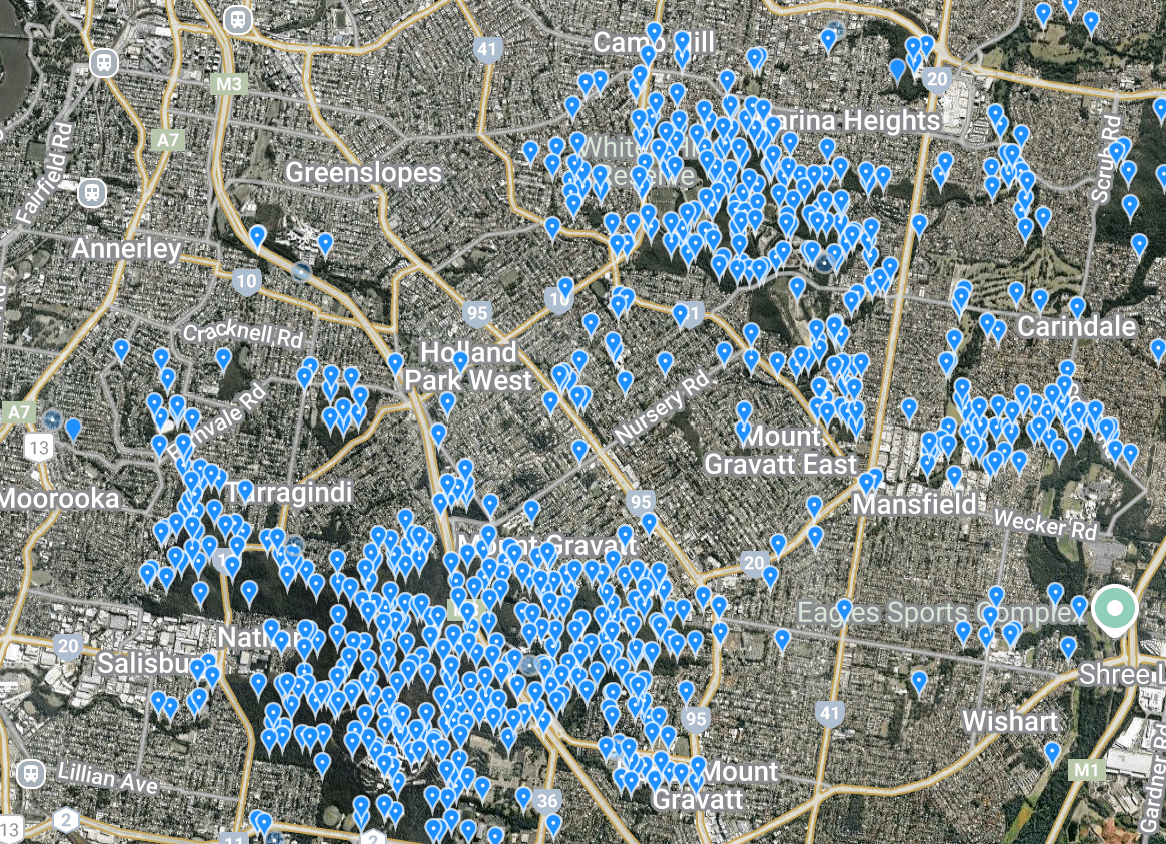

But today in Toohey Forest, koala populations are growing steadily on both sides of the M3 motorway, and the marsupials are increasingly spreading beyond the reserves and across the suburbs. Based on reported sightings and movements (which only provide a partial picture of all the places koalas are moving to), it looks like koalas from Toohey/Mt Gravatt are now pretty close to linking up with the more established population in Whites Hill bushland reserve (if they haven’t already done so).

Unfortunately, they're also frequently being hit by cars.

Various sources suggest that the reappearance of koalas in Toohey Forest is primarily due to under-the-radar relocations by wildlife rescuers. One former state government employee told me that in the 90s and early 2000s, even the Queensland government itself routinely relocated lost koalas to the nearest, most convenient bushland reserve, regardless of whether officials knew the site was suitable koala habitat.

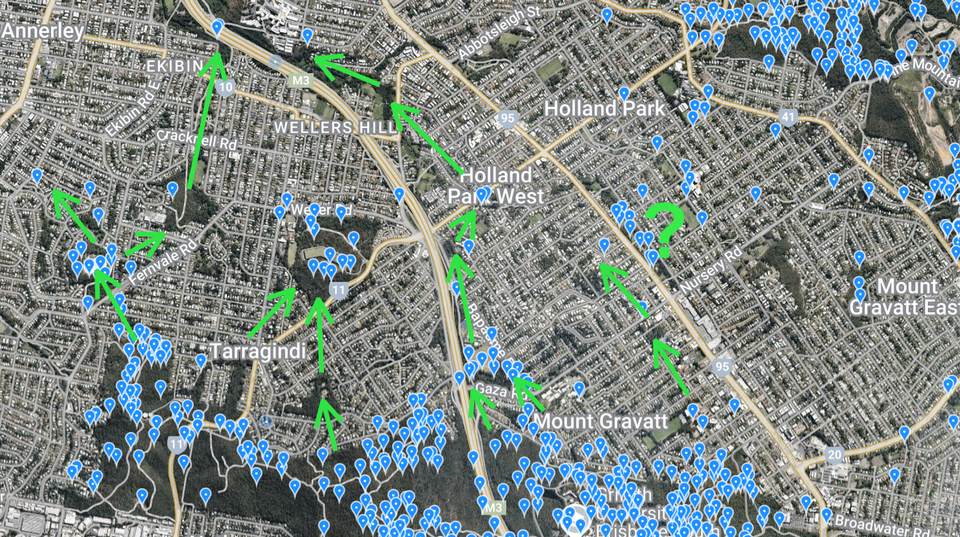

Koalas have been roaming from Whites Hill across Coorparoo, Holland Park, Camp Hill and Mt Gravatt East for many years now, but now they’re increasingly being seen not just in Tarragindi, immediately to the north of Toohey Forest, but in parts of Moorooka, Salisbury, Holland Park West, and even the edges of Annerley and Greenslopes.

That's right – koalas have been repeatedly sighted just a 5-minute drive south of the Brisbane CBD.

Ten or fifteen years ago, I would’ve considered it pretty unlikely that koalas could become a regular occurrence in Brisbane’s inner-south side, but it turns out Toohey Forest koalas are tenacious, intrepid little buggers. Under cover of darkness, they roam the suburbs much further than most people realise.

To repurpose an old aphorism – the koala isn’t crossing the road, the road is crossing the forest.

Just a few generations ago, much of Annerley, Fairfield and Greenslopes would’ve been solid koala habitat. The soil on which their eucalyptus woodlands once grew is still there under the roads, driveways, houses and swimming pools.

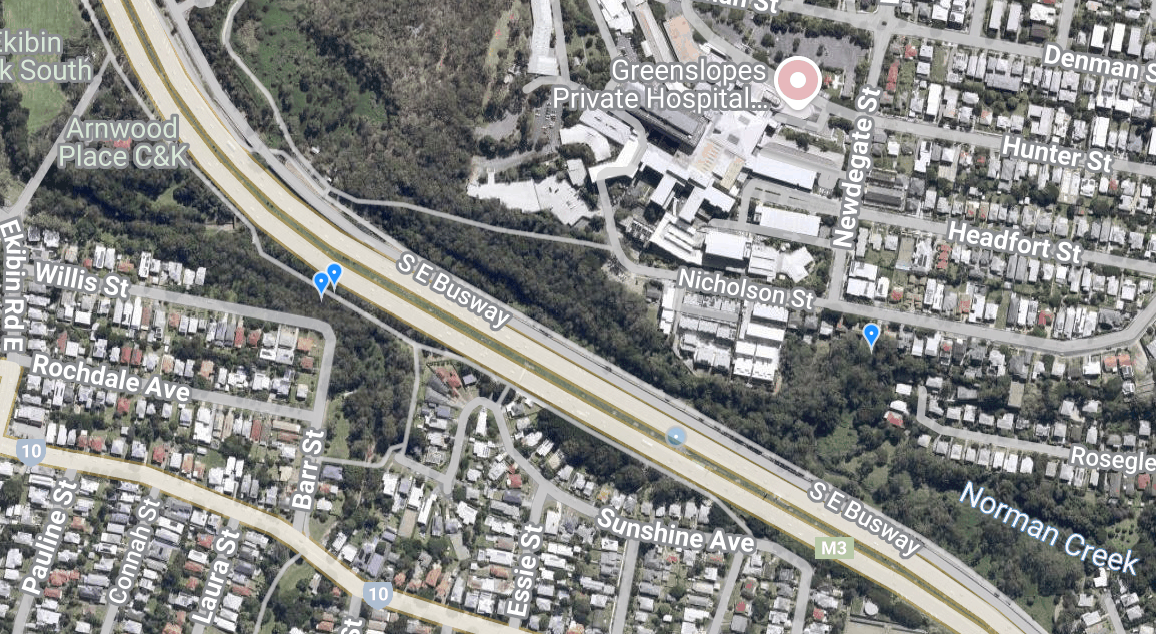

Over the past 18 months, individual koalas have been photographed (admittedly on only a couple of occasions) as far north as Barr Street Park (on the south/west side of the Pacific Motorway), and in the bushland behind Nicholson Street at the southern end of Greenslopes (which is on the north/east side of the motorway). They’ve also repeatedly made it to streets around Clifton Hill in southern Annerley.

Meanwhile Whites Hill koalas are now occasionally moving west across Cavendish Road, towards the eastern side of Greenslopes.

Of course, modern Australian suburbia can be pretty hostile to koalas. The biggest threats are fast-moving cars and large dogs.

But while the city council’s urban planners and traffic engineers might insist on a clear distinction between bushland reserves and residential areas, koalas evidently aren’t as concerned about where the City Plan zoning maps say they should go.

As their numbers increase, they'll continue pushing out of Whites Hill and Toohey Forest, and eventually – if they aren't mowed down by cars – into neighbourhoods where the marsupials haven’t been seen for 100 years.

Where are they moving?

Brisbane koalas favour areas that are well-watered – they tend to prefer creek corridors and gullies rather than ridges and hilltops (although having said that, I frequently observe koalas around the summit of Mt Gravatt). If eucalypts are growing in nutrient-poor soil, or their leaves don’t have enough moisture content, they won’t be a palatable source of food (there are lots of factors shaping which leaves koalas will and won't feed on, especially their specific gut biome – it's not the case that individuals will happily feed on every tree of a particular eucalyptus species). Importantly, the animals also use non-eucalyptus shelter trees with thicker canopies, whose shade offers more daytime protection from the sun than gum trees (this is why koalas are often spotted resting in trees that they can’t feed on).

While they’re much safer from dog attacks when they’re up a tree, and they certainly prefer habitats where trees are closer together, koalas will often travel a couple hundred metres across the ground between trees if they have to.

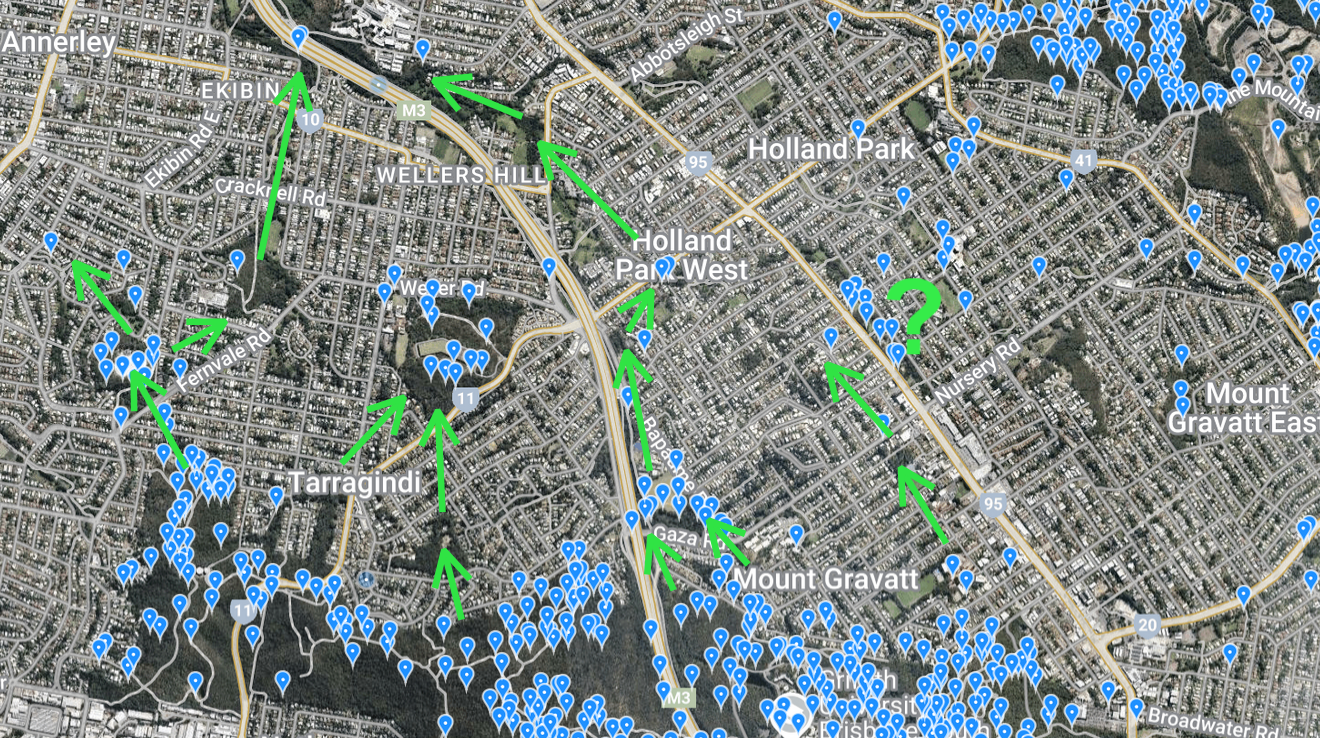

In this map, I’ve roughly sketched out the routes that I think koalas are increasingly moving along through Holland Park West and Tarragindi towards Greenslopes and Annerley. Kulpurum/Norman Creek and its tributaries is the most important corridor, but they’re also using other chains of parks, school-grounds and leafy backyards.

Schools in particular seem to be important stepping stones through suburbia, as they are large, often-leafy sites that are mostly empty of people (and dogs) at night (unfortunately, as the impending koala habitat destruction at Ormiston College in the Redlands shows, schools are not as safe from development as bushland reserves).

Most of the koalas pushing through the suburbs are males looking for new territory, but breeding females and mums with young joeys have also been seen outside the existing bushland reserves.

Where there’s a high enough density of healthy koala food trees, with good soil and enough moisture in the landscape, a female koala can raise a joey in a forested area of as little as 1 to 2 hectares. If koalas can freely move between forest reserves to find new mates and maintain genetic diversity, urban populations could be sustainable long-term.

Where can they breed?

Looking at how they’re spreading year by year, it seems plausible to me that if humans can stop running them over with the massive battering rams most of us drive around in, koalas could establish a breeding population in the connected green spaces of Stephens Mountain Reserve, the Greenslopes DCP site, Roseglen Street Park and the Birdwood Rd corridor park over the coming decade (for convenience, I’ll refer to this site as the Greenslopes Forest, conceding that at just over 20 hectares, it’s pretty small for the label ‘forest’).

Greenslopes Forest already features a solid population of established eucalyptus trees, is well-watered by Norman Creek and its tributaries, and is theoretically large enough to serve as a year-round home for multiple breeding female koalas, particularly if the city council or motivated local residents planted even more gum trees in place of the weed trees that have overtaken some parts of it.

Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee has undertaken significant habitat restoration work in the Greenslopes DCP section of the forest over many years, with another major round of weed clearing and tree planting now underway.

In 2024, a lone koala was photographed in Greenslopes Forest, just south of Nicholson Street. It’s not clear exactly what route the animal travelled to get there, but considering the formidable barrier of the Pacific Motorway, it was likely along the Norman Creek corridor through Holland Park West.

Planting more koala food trees along this corridor – particularly in Joachim Street Park – will support koalas to move north along Norman Creek, and hopefully help draw them away from trying to cross the Pacific Motorway. Even more important would be the introduction of significantly lower speed limits on the main roads that intersect the koala’s movement corridors towards Greenslopes, including stretches of Gaza Road/Nursery Road, Sterculia Avenue, Logan Rd, Marshall Rd and Birdwood Rd.

If koalas do begin breeding successfully in Greenslopes Forest, it’s likely we would eventually also see some individuals roaming further north along Norman Creek through Ekibin Park and Hanlon Park. I can imagine lots of Greenslopes residents would love this. But my interest here is not simply in seeing a dozen or so lonely koalas stuck in Greenslopes Forest, wondering why every time they head further north they encounter more buildings than trees...

Reimagining suburbia’s relationship to the nonhuman

It's important to emphasise that across Queensland, and particularly on Brisbane's outer-suburban fringe, eucalyptus woodland – prime koala habitat – is still being cleared at a phenomenal rate. Koalas are in decline (primarily due to habitat loss, and exacerbated by car strikes and dog attacks) and some claim the marsupials are on track for local extinction in South-East Queensland unless we stop cutting down trees and start planting more (it's a very different story in Victoria and South Australia, where stronger environmental protections are supporting koala numbers to continue growing).

Crucially though, Brisbane City Council doesn't currently include any eucalyptus species in its list of approved species for new street tree plantings. The only trees on the list which might be considered as secondary food sources for koalas are brush boxes (Lophostemon confertus) and broad-leaved paperbarks (Melaleuca quinquinervia) which the marsupials sometimes use as a medicinal tree. This means that even on roads with wide verges, minimal foot traffic and plenty of space for big eucalypts, the council is not planting any new trees that koalas could routinely feed on.

At a time of so much ecological destruction and loss, the fact that koalas in one part of Brisbane seem to be breeding successfully and expanding their territory rather than dying out is a valuable counterpoint to the “why even bother?” defeatism that capitalism – and particularly the property industry – so often directs towards proposals for environmental restoration.

The return of koalas to Toohey Forest and surrounding suburbs is an invitation to reimagine our neighbourhoods – to ask what would have to change for koalas (and many other species) to be able to survive not only in loosely connected strings of parks and small bushland reserves, but in the actual backyards and streets of residential suburbs.

Many of the most obvious required changes would benefit a wide range of native species, but would arguably also improve quality of life for us humans...

Lowering speed limits – ideally to 30km/h in neighbourhoods that koalas are moving through – is the most pressing necessary improvement. On many streets, bitumen roadways could also be narrowed to create wider footpaths. This would allow more room for larger street trees (including the various eucalyptus species that local koalas feed on).

I should emphasise here that speed limit reductions are a much simpler and more cost-effective measure than installing expensive wildlife bridges. We're never going to get koala-friendly wildlife bridges over every road that koalas are trying to cross, but if motorists slow down, the casualty rate will drop dramatically.

Preserving existing trees in backyards is crucial, as is requiring developers to set aside a much larger proportion of redevelopment sites as green space with deep-planted trees.

Making suburbs leafier and less car-centric improves quality of life for human residents, while also inviting animals like koalas back into our communities.

Other helpful changes, such as reducing light pollution by turning off non-essential outdoor lighting, and keeping dogs indoors at night (or at least fenced in such a way as to reduce the likelihood of them attacking koalas that are moving through backyards) don’t ask very much of us.

In urban areas, good environmental conservation can't stop at protecting public parks and nature reserves – we need a new, more equitable balance of the space taken up by human dwellings, and the spaces in between that animals can exist in.

Many committed conservationists would understandably argue that the resources and effort required to make suburbia friendlier to a wider range of native animals would be better focussed on conserving and restoring habitat in rural areas. But this isn't a binary choice. In practice, I don't see any evidence that arguing for the protection and restoration of green spaces and wildlife corridors in Brisbane comes at the expense of funding or advocacy capacity to protect against land-clearing for coal mines or cattle grazing elsewhere in the state.

But more importantly, there's a lot of cultural, social and political value in creating urban neighbourhoods where people feel a close connection to the non-human and the 'natural'.

If a resident of Annerley can look out their window and see a koala up a tree at the bottom of their yard, that necessarily shapes their broader view of the world, and probably increases the chance that they'll also care about protecting other natural spaces further afield.

Suburban sprawl development typologies, with relatively low-density homes taking up huge areas of land, are ordinarily one of the most ecologically destructive forms of housing. But if we can find ways to ensure the spaces between houses – i.e. yards, median strips, roadways, footpaths, drainage easements – are well-vegetated and safe for wildlife to move through and even breed in, suburbia need not be an ecological wasteland.

This koala had crossed busy Gaza Road to reach this stretch of trees beside Holland Park State High School

There's a lot that all levels of government – including Brisbane City Council – could be doing to create and preserve more habitat space for koalas and other native animals across our urban footprint. But for the average resident reading this, here are a few steps you can take to help the cause:

- plant koala habitat trees wherever you can find the space... the non-profit Paten Park Native Nursery at the Gap is an affordable source of a wide range of eucalyptus seedlings, or check out Brisbane City Council's free native plants program (you can get two plants per year)

- volunteer with Norman Creek Catchment Coordinating Committee on local habitat restoration projects – if you sign up as a member for just $10/year, you're also entitled to ten free native seedlings from N4C's nursery in Greenslopes (you could ask for koala trees and plant them in suitable spots)

- drive slower than the speed limit around parks and bushland reserves, particularly in the evenings and early mornings

- write to local councillors (Krista Adams, Councillor for Holland Park Ward and Fiona Cunningham, Deputy Mayor and Councillor for Coorparoo Ward) asking them to:

- plant more koala food trees in Joachim Street Park

- add koala-friendly eucalyptus species to the council's street tree planting list, and

- support lowering speed limits on Boundary Rd (beside the Whites Hill reserve), Gaza Road, Sterculia Avenue, Marshall Rd and Birdwood Rd to facilitate safer movement of koalas and other native animals - email Joe Kelly, State Member of Parliament for Greenslopes, to ask him to support the above-mentioned speed limit reductions, to advocate for more eucalyptus tree planting in Department of Transport-owned land alongside the Pacific Motorway, and to update the State Government's koala habitat area mapping to better reflect the movement of koalas and the presence of existing eucalyptus trees along the Norman Creek corridor

- log any koala sightings via a non-profit public platform like iNaturalist

I should end by reminding readers that there are heaps of other native species at far greater risk of extinction than koalas, and other ecosystems in our region which are even more degraded and depleted than eucalyptus woodlands, but which attract less government support and attention from conservation groups. That obviously doesn't mean we shouldn't care about koalas or eucalyptus forests – it's simply a reminder that our efforts mustn't become too narrow in focus.

Down in Adelaide, more concerted conservation work has led to koalas following creek and river corridors right into the city centre. So if we plant more trees, drop speed limits and protect green corridors, it's not farfetched to imagine that one day koalas could become regulars in Annerley and Greenslopes, and maybe even Dutton Park, Fairfield and Yeronga, not to mention Barrambin/Victoria Park in the inner-north side.

The struggle to protect and restore threatened species and ecosystems is global, but we can start right here on our own doorstep.

Note: In this article, I haven't bothered including direct source links for widely-accepted facts about koala behaviour, but if you're looking for a deep dive into that stuff, I recommend the 2022 book Koala: A Life in Trees by Danielle Clode

Thanks for reading! If you're interested in this sort of stuff, you might like to subscribe to my newsletter to receive updates on future articles.

Member discussion