Court challenges alone won’t save Barrambin, but could the Save Victoria Park campaign find a radical edge?

On Saturday, 19 July, several dozen people gathered beside the Ibis Island waterhole at the southeast end of Barrambin/Victoria Park to share knowledge and strengthen their commitments to protecting Brisbane’s largest inner-city green space from the Olympics juggernaut.

This wasn’t a mass demonstration intended to attract media coverage, but a relaxed social event for people to build connections to each other and the park.

DJs played beats on a battery-powered sound system. Participants made art, shared food, and drank tea. A few keen environmentalists led people on tours of some of the oldest trees that will be removed if the stadiums are built over the park (yes, the government is proposing multiple large venues, not just one), and I was invited to share some poetry.

This event wasn’t organised by the larger advocacy group Save Victoria Park Incorporated, but by a couple of activists connected to 4ZZZ Eco Radio and Wildlife Ambulance Magan-Djin. Although the turnout was small, attendance seemed more demographically diverse than some of the previous Save Victoria Park events I’ve been to, with a few more of the old-school hippies and anarchists (who mostly can’t afford to live in inner-Brisbane these days) travelling in from places like Mt Tamborine, Bribie Island and the Gold Coast, as well as the middle-aged, middle-class inner-city residents who have been the most prominent constituency of opposition so far.

It wasn't an especially remarkable afternoon, but I thought the We’re Going to Ibisa picnic was worth a mention, because it marked one of the first occasions that the campaign to save the park showed glimpses of a more radical streak, which seems to have been missing until now...

DJs and the discussion circle

Back in late 2023, a snowball of public opposition to demolishing and rebuilding the Gabba for the Olympics contributed to Annastacia Palaszczuk stepping down from her role as Premier.

Leading into the 2024 Queensland state election, resistance to spending billions on new stadiums was so strong that David Crisafulli and Steven Miles both repeatedly ruled out building any stadiums at Barrambin.

Today, as the government claims it doesn’t have the money to sufficiently fund healthcare, education, public housing and public transport, scepticism of the Olympics and opposition to wasteful spending on white elephant inner-city vanity projects remains high, with petitions against the LNP’s Victoria Park stadium proposal attracting thousands of signatures.

Yet actual protest on the ground has been comparatively muted.

Perhaps never in Brisbane’s history has such a costly and ill-considered mega-project attracted so little direct action pushback. Why is this?

There’s lots of other stuff to protest against, from new fossil fuel projects, to cops killing Aboriginal people, to Australian weapons components being used to murder civilians in Gaza.

But that alone doesn’t explain why a proposal to waste billions of dollars destroying one of South-East Queensland’s most culturally significant Aboriginal sites, cutting down hundreds of mature trees, selling off hectares of public land for private development, and concreting over Brisbane’s largest inner-city parkland hasn’t been the target of more vigorous and sustained grassroots protest.

There’s another, larger factor at play that we need to learn from: the main community campaign entity – Save Victoria Park – has, I think, been too cautious about breaking laws and making waves, and so might be inadvertently diverting the broader community away from more effective forms of direct action protest.

When supporters ask "is it time to organise a bigger, more disruptive protest?" or "what else can we do?" they're sometimes forming the impression from their engagement with SVP that protesting isn't the main focus, and that we need to place our faith in legal challenges. Other entities, such as NGOs and Greens politicians, follow this lead, so if the local community campaign isn't orienting towards civil disobedience, no-one else is going to call for it either.

Save Victoria Park is an entirely volunteer-led independent community organisation that’s been doing great work for several years now. They’ve been effectively researching and exposing the details of just how messed up the stadiums plan for Barrambin really is, organising petitions and submissions, holding community meetings and press conferences, lobbying politicians directly, and fundraising successfully for court challenges. The many resources they've produced tell a powerful story of the park's cultural and historical significance.

But to win a campaign like this, against such a massive project with tight timelines and blank cheque budgets, the harsh reality is that petitions, press conferences, well-attended community meetings and powerful storytelling simply aren’t enough. You need to hit the streets again and again and again to build momentum and create a political crisis for the government. And you need a robust and effective campaign strategy.

Governments write laws – courts just flesh them out

Before I studied law at university, I thought courts had a lot more power than they actually do. Pop culture often teaches us that if you challenge something in court, justice may well prevail, and the judge will rule against the corrupt politicians and greedy corporations.

But here in the real world, the judiciary is – broadly speaking – subservient to the legislature. That means if a court says "hey government, you can't do this because it's against the law" most of the time, the government can just write new laws.

Over the years, I've watched this rewriting of the rules occur regularly in the urban planning space...

- Profit-hungry developer applies to build something that violates current planning rules for that area – such as building height limits.

- The developer-friendly Brisbane City Council approves the development anyway.

- Residents successfully challenge the approval in the Planning and Environment Court, and the approval is overturned.

- A year or two later, Brisbane City Council updates its City Plan to relax planning rules and increase the height limit for the precinct in question, or perhaps the State Government introduces a new, more permissive planning instrument that overrides the City Plan.

- An amended version of the previous development proposal is approved, but this time residents don't even have legal standing to challenge the approval.

We're already seeing this play out with the Olympics. Queensland's LNP government recently passed legislation to exempt Olympic venue projects from a long list of laws and regulations which might otherwise have served as grounds for legal challenges (ironically, they simultaneously tightened planning regulations for solar and wind farm projects – a reminder that planning frameworks are always political).

Save Victoria Park is still fundraising for legal costs. It's not clear to me what the basis of any future legal challenges might be, but they evidently have a few pathways in mind that they're not speaking about publicly.

Even if their lawyers do come up with potential legal arguments to halt the stadium, there's not likely to be anything stopping the state or federal government from introducing further legislative changes to outflank those court proceedings.

That's not to say that court challenges have no strategic value. They can add to the cost and complexity of a particular project and drag things out. They can help maintain media interest and serve as a platform to articulate key concerns with a proposal. Interim court victories can even strengthen a campaign's moral case.

But while fundraising for lawyers to run cases is helpful, stopping the Olympics juggernaut ultimately requires a political victory, not just a legal one.

Federal ministerial intervention?

There's some hope in applying to the federal Environment Minister, Murray Watt, to intervene and declare the site protected as a significant Aboriginal area – that's what Save Victoria Park is currently putting its funds towards.

While it certainly doesn't hurt to pursue this avenue, Minister Watt already has form prioritising the interests of big corporations ahead of the community and the environment. The application to his department unlocks a lever that the federal government can use to come in over the top of the Queensland LNP, but they'll only pull it if political pressure is strong and widespread enough.

In practical terms, the application by Yagara Magandjin Aboriginal Corporation under section 10 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 cannot force the minister to protect the park if he and his party don't want to.

The federal Labor government has already signed a new Olympics funding agreement with Queensland's LNP government that effectively confirms Labor's support for the Barrambin stadiums. Whereas for the previous funding agreement, federal Labor at least signalled reservations about supporting the Woolloongabba stadium reconstruction, there appears to be no similar hesitancy regarding Barrambin.

It seems like a minor strategic oversight that Save Victoria Park didn't focus on pressuring federal Labor MPs in the lead-up to this decision (why weren't there sit-ins and protests outside MPs' offices?).

But more importantly, this new funding agreement means political pressure against the destruction of Barrambin would have to reach a much higher threshold for Murray Watt to step in and effectively counteract the decision his government just made.

Olympic fence-sitting won’t win it

I have a lot of time for Save Victoria Park. I don't want to be misconstrued as attacking them or talking down the thousands of hours of volunteer labour their core organisers have put into the campaign. Like many community campaigns, most of the obvious limitations to what they're doing are probably just a result of limited volunteer capacity.

But my main disappointment with the group so far has been its reluctance to articulate a strong critique of the Olympics as a whole, or even of the idea that new stadiums are a good thing to waste resources on.

SVP spokespeople have repeatedly insisted that they’re not anti-Olympics, and that they’re not even against building new Olympic venues in other locations, but simply that they don’t want any stadiums in Barrambin. Unfortunately, this makes it easier for stadium proponents to pigeonhole the campaign as NIMBYISM.

While most core organisers of the somewhat successful campaign against a Gabba Olympics stadium were primarily motivated by local concerns about green space losses, school closures, and construction impacts in the surrounding neighbourhood, it was the phenomenal cost of the project – both in terms of dollars and non-renewable resources – that stoked broader statewide opposition. People from across Queensland who probably didn’t care much at all about East Brisbane State School, Raymond Park or Woolloongabba Place Park objected to such huge infrastructure expenditure in an inner-Brisbane suburb simply on value-for-money grounds.

Most Queenslanders living outside inner-metropolitan areas don't currently experience green space shortages as a major issue. However by highlighting and arguing against the huge stadium cost – which is ultimately worn by the wider public – the Gabba campaign was able to remind people from further afield that they too would lose out as a result of the proposal.

But I describe the Gabba stadium campaign as only 'somewhat successful' because it too failed to articulate a robust critique of the wastefulness of the Olympics as a whole, and didn't successfully convert the groundswell of opposition to a Gabba Olympics into a broader campaign for a low-cost, low-impact games that puts ordinary people's needs before corporate profits. Consequently, it now looks like the LNP may sell off many hectares of publicly-owned land in Woolloongabba for private development in order to cross-subsidise their more expensive Victoria Park proposal.

Meanwhile some (though not many) opponents of the Barrambin stadiums have even resorted to calling for a Gabba Olympics (despite the likely severe impacts to parkland and local schools). Arguing against a new stadium in your suburb, but not arguing against Olympic waste more generally, plays directly into the LNP's and the International Olympic Committee's divide-and-conquer strategy.

This flawed thinking was clearly evidenced in comments by former LNP Premier Campbell Newman – a notorious ally of big property developers – at Save Victoria Park's community meeting on Monday, 18 May. In response to a resident's question about whether the community should be exploring other forms of protest and direct action delay tactics, he said "I don't see that we've got the means to delay the project per se" (I think he's completely wrong on that front). Instead, he told attendees that "if we speak up loudly and clearly... if we talk to people of influence around town..." somehow the government would just magically change its mind.

There's an incredible level of hubris and naivety underlying such comments, that perhaps helps illustrate why Newman lost government after only one term in office, and why other politicians on his own side of the political spectrum no longer consider him an effective strategist.

The problem for Save Victoria Park is that if we don't win the broader argument against the Olympic drive to build major new venues, Barrambin ends up being one of the cheapest, most viable available options within Brisbane, because the government already owns the land.

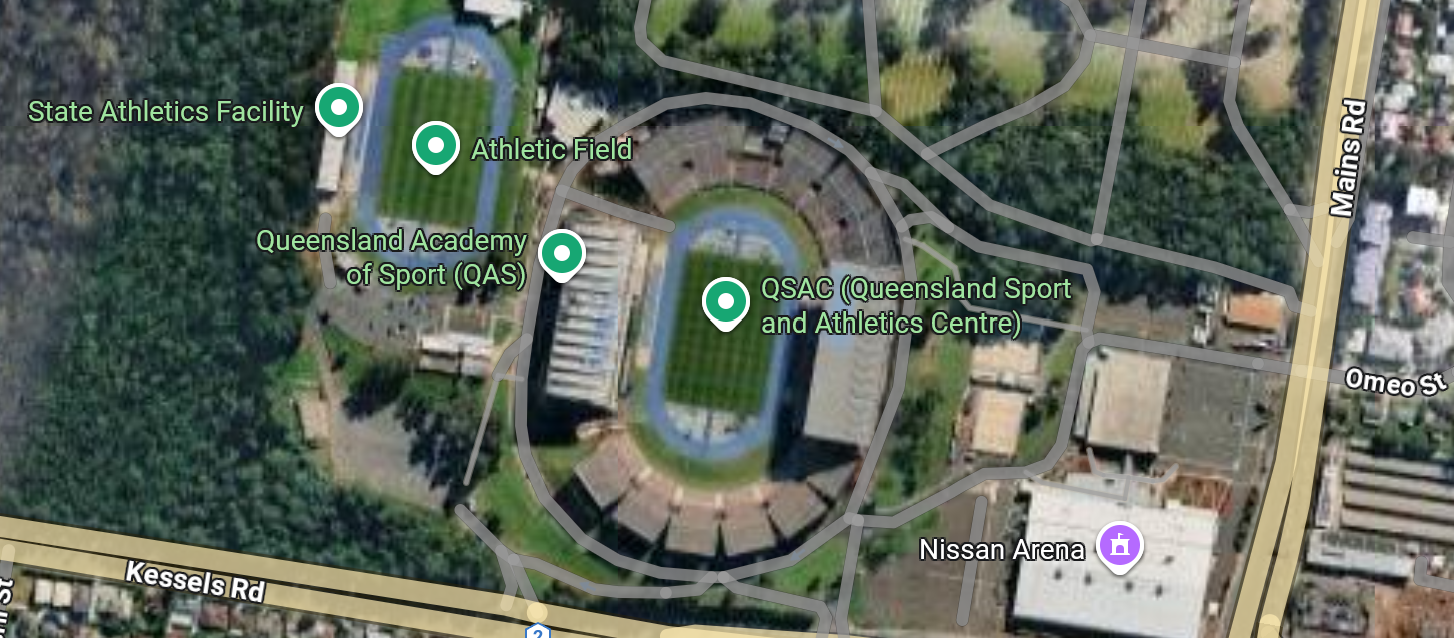

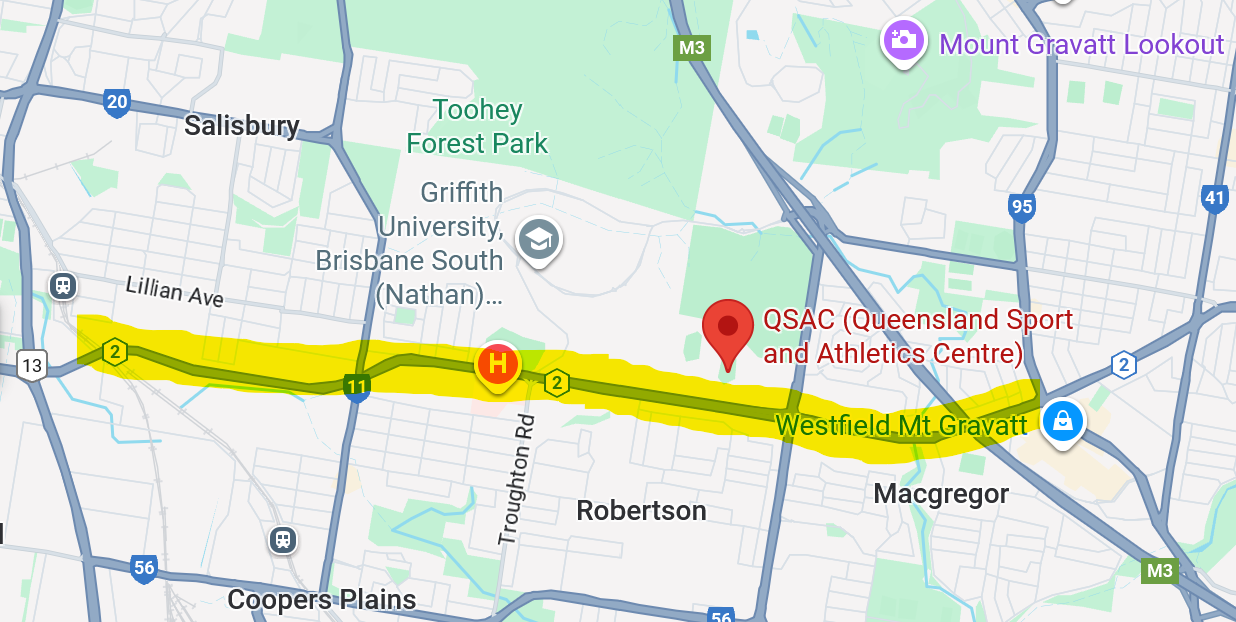

Personally, I don't think we do need a new athletics stadium. South-East Queensland already has multiple major stadium venue options, including QSAC at Nathan, and Carrarra Stadium on the Gold Coast. For a fraction of the cost of building new stadiums (including warm-up tracks and ancillary facilities) at Victoria Park, the Nathan venues (which, unlike the space-constrained Gabba site, already have an athletics warm-up track) could be upgraded without negative impacts to existing parkland or a busy inner-city hospital precinct.

Imagine, for a moment, if Nathan became the preferred location... A fraction of the billions of dollars the government currently proposes to waste levelling and filling the slopes and waterholes of Barrambin could instead be invested in constructing light rail along Riawena and Kessells Roads, which would connect Mt Gravatt's Garden City precinct and the M1 Brisbane Metro line to the Nathan stadium, Griffith University, QEII hospital and the Beenleigh train line. This would enable government-led development of public transport-supported, mixed-use medium-density housing in a part of southern Brisbane that's currently very low-density (anyone arguing that Nathan is 'too far' from Brisbane's CBD would do well to remember that Sydney's Olympic Park precinct is 20 kilometres from central Sydney).

But the intention of this article is not to argue strongly for any particular alternative stadium location (personally I'm still in the 'Brisbane should cut our losses and pull out of hosting the Olympics altogether' camp). I'm simply highlighting that it would be better to spend billions of dollars on public transport infrastructure and public housing than on building new stadiums.

But if Save Victoria Park tacitly accepts that entirely new stadiums are needed to host the Olympics, and it's simply a question of location, their argument becomes much less compelling.

This narrow thinking – not wanting to be perceived as 'anti-Olympics' – reflects the upper-midde-class sensibilities that seem to dominate the campaign, but which risk leading residents down a strategic dead-end.

Wishful thinking vs Building a bigger coalition

On many occasions during my 7 years as a city councillor, I encountered groups of residents (mostly but not exclusively real estate-owning, middle-class, comparatively privileged types) who were convinced that if they avoided 'divisive' tactics like disruptive protests, and maintained a sufficiently 'mainstream' image, they could overcome the combined might of the big end of town. Time and again, these approaches proved ineffective.

For a community campaign to succeed on such terms, you need to turn your cause into a major election issue that's likely to swing so many votes and seats (I'm talking tens of thousands of votes) that the government becomes worried about losing power, and shifts its position in response.

But there are no local, state or federal government elections due until 2028. So a community campaign that relies primarily on a "don't look too radical and don't offend anyone" strategy has very little leverage in this respect.

Even if tens of thousands of residents from Sunnybank to Sandgate were vocally opposed to the Victoria Park Olympics plan, that public sentiment alone wouldn't be enough to shift government decision-making. The Olympics is just too big. Remember that during the height of the covid pandemic, when public opposition to Tokyo hosting the summer Olympics climbed to epic heights, the games still went ahead.

Awareness-raising simply doesn't cut it. Merely "talking to influential people" as Campbell Newman suggests, isn't sufficient. Popular sentiment has to be translated into practical collective action that forces the government to change course.

There's still a pathway to victory for those of us who don't want to see Barrambin destroyed. It would involve some combination of:

- significant numbers of construction, engineering and design workers deciding that they don't want to work on the stadium projects on ethical grounds – basically some kind of green ban

- companies that might tender for Olympics contracts deciding that the risk to their brand/reputation of working on projects in Barrambin outweighs the rewards (particularly when there are so many other major projects they could work on instead) – this would require ongoing protests that target these companies directly

- athletes – particularly First Nations athletes – declaring that they're uncomfortable competing at a stadium whose construction involved major degradation of a culturally and environmentally significant site

- a credible threat of mass civil disobedience – including tree-sits, lock-ons and blockades – that raises the likelihood of delays to construction

- large numbers of regional Queensland MPs and federal MPs in other states rebelling against the proposal due to escalating costs and perceptions that too much white elephant infrastructure spending is being sunk into South-East Queensland

There would of course also be value in pressuring city-based Labor MPs – particularly those in seats like Griffith, Brisbane, Bonner and Lilley – to signal to the federal Labor government that it should withdraw its support for a Barrambin Olympics. But Labor considers seats like Griffith and Brisbane expendable, and believes it would be able to retain government after 2028 even if it lost these two seats to the Greens.

For the above conditions to materialise – particularly construction workers considering green bans, and hundreds of protesters being willing to risk arrest for crimes such as trespass – the campaign to Save Victoria Park needs to appeal to the interests and concerns of lower-income renters and working class people who by and large can no longer afford to live near Barrambin.

It may be true that a strategy which eschews disruptive protest and avoids a broader critique of the Olympics is best-adapted to appeal to middle-class inner-city residents who live in suburbs around the park. But that constituency isn't actually the most important one to this particular struggle unless those residents are willing to engage in exactly the kinds of disruptive protests that Save Victoria Park isn't well-equipped to deliver and endorse (in fact, aligning yourself with someone like Campbell Newman – who is widely hated by so many of the construction workers and environmental activists you ultimately need to win over amd mobilise – is arguably an own goal).

Barrambin is one of the only public spaces in inner-city Brisbane where I regularly see cockatoos

Personally I don't think it's too late to save Barrambin. Covid showed us how quickly the world can change, and a lot can happen between now and 2032.

But any hope of victory lies in first discarding the middle-class sensibilities that a) devalue civil disobedience tactics, and b) prioritise arguments that resonate with other inner-city, property-owning residents, but don't tap into wider anti-establishment and anti-Olympics sentiment across the state.

A lesson for other struggles

I'm interested in all this not only because I desperately want to see Barrambin saved and preserved as a space of outdoor recreation and native habitat restoration, but because I think it's important to unpack how and why so many campaigns end up adopting wet blanket strategies that discourage civil disobedience, or only embrace disruptive protest tactics when it's too late.

Community campaigns sometimes say they don't want to organise disruptive protests because "they don't want to jeopardise their legal strategy." Frankly I don't see how such an argument would make sense in a context where Save Victoria Park hasn't even initiated court proceedings. Organising disruptive protests wouldn't undermine the ministerial application under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act in any way.

But SVP's apparent disinclination for more controversial forms of civil disobedience shows us how the existence of an incorporated community association that adopts a campaign strategy focussed on court challenges actually risks crowding out the space for more radical and effective forms of protest.

It makes me wonder whether, if SVP didn't exist, other more radical anti-Olympics groupings would have emerged to contest the Barrambin stadiums proposal more strongly.

Plenty of supporters of Save Victoria Park are certainly ready and eager to escalate protest action. But because SVP is the central node of the campaign, in control of email lists and the largest communication channels, it's hard for anyone else to build a direct action-oriented campaign against the park without their support.

Since the We're Going to Ibisa picnic a month ago, a few other radical anti-stadium events have started popping up. It would be great if these blossomed into regular direct action training sessions, guerilla native tree planting days, and public education not just about the importance of green space to local residents, but the broader, significant ecological and global warming impacts of building new stadiums in any location.

A decentralised campaign ecosystem where many different groups and individuals are organising a variety of actions in opposition to new Olympic stadiums across Brisbane has a much better chance of succeeding than a narrower court-focussed trategy.

But the clock is ticking.

So perhaps it's time to break out the d-locks.

I feel really grateful that so many people have been reading my articles and engaging with the thoughts I'm sharing with the world. If you'd like me to spend more time on this, please consider supporting this work by subscribing to my semi-regular newsletter.

Oh and if you're reading this article before 27/09/25, you should also try to get along to the Ibisa Sunset event – a Saturday afternoon/evening dance party in the park.

Member discussion