Anarchy in the riparian zone: Does liminal life fertilise radical imaginations?

Living in hyper-bureaucratised, capitalist cities like Brisbane, many of us treat the coercive regulatory power of government as inevitable and ubiquitous.

It’s almost like we each carry a bossy little city council inspector around in our head… “Oh that community orchard/street party/DIY skate park/pop-up art gallery idea sounds cool, but think of all the paperwork!” we say to each other. “You'll never get council permission for that!”

A world where governments and corporations have far less control over our lives is becoming progressively harder to imagine.

So one of the unexpected joys of living on our off-grid houseboat for the past 8 years has been the experience of feeling just a little further beyond the regulatory reach of government, despite our proximity to the inner-city.

See, every time we scramble down the creek bank through the mangroves to access our boat, we cross an invisible barrier between worlds.

On one side, there’s the public roadway... a suburban street controlled and maintained by Brisbane City Council, subject to all the usual road rules and design regulations.

On the other side… the riparian zone.

This clip was filmed less than 2.5km from Brisbane’s CBD, but with flying foxes circling overhead and ibis chicks squawking in their tangled nests, it feels like a world away

Riparian zones are the liminal spaces between land and water – the mudflats of the river’s floodplain, the swampy marshes, the mangrove fringes, the sloping creek banks.

In tidal waterways like the creek we moor our boat on, a significant chunk of the riparian zone is only submerged during the highest tides of the month, and stays dry(ish) the rest of the time.

Politicians, lawyers, developers, urban planners and real estate agents tend to like pointing at places and saying “that bit’s land, and this bit is water.” But waterways flex and shift over time – they don’t naturally conform to rigid boundaries. Riparian zones subvert and mess with top-down attempts to define, control, and parcel up natural environments.

For centuries, property lawyers in particular have argued over definitions of riparian zone boundaries... Is it the average high tide mark? The highest high tide mark of the year? Or maybe the creek’s occasional highwater mark during heavy storms and flash floods? They still don’t all agree.

@jonnosri We've got to stop approving new development on land that's vulnerable to flooding and recognise that in some areas, the cost of maintaining basic infrastructure will skyrocket due to sea level rise, even when we're NOT impacted by severe storms. #globalwarming #fossilfuels

♬ original sound - Jonathan Sriranganathan

In some areas, the true riparian zone arguably extends well beyond the mapped boundaries of the waterway itself, and across surrounding streets

Historically, the floodprone and erosion-prone nature of Brisbane’s riparian zones protected them somewhat from privatisation and over-development. Even as trees were felled and land was cleared across the urban footprint, densely vegetated wildlife corridors persisted along many creek and river banks.

Throughout the first century of the European invasion of South-East Queensland, resource-abundant riparian zones (and their littoral seaside equivalents) remained crucial foraging grounds and strongholds where Aboriginal people were able to continue living wholly outside the capitalist colony’s economic and legal systems – a recurrent pattern for non-state peoples across the globe.

Sadly, newer development projects along Maiwar’s inner-city reaches are shrinking this zone; vertical concrete banks seek to tame waterways and define sharper boundaries between river and land (which is often privatised in the process).

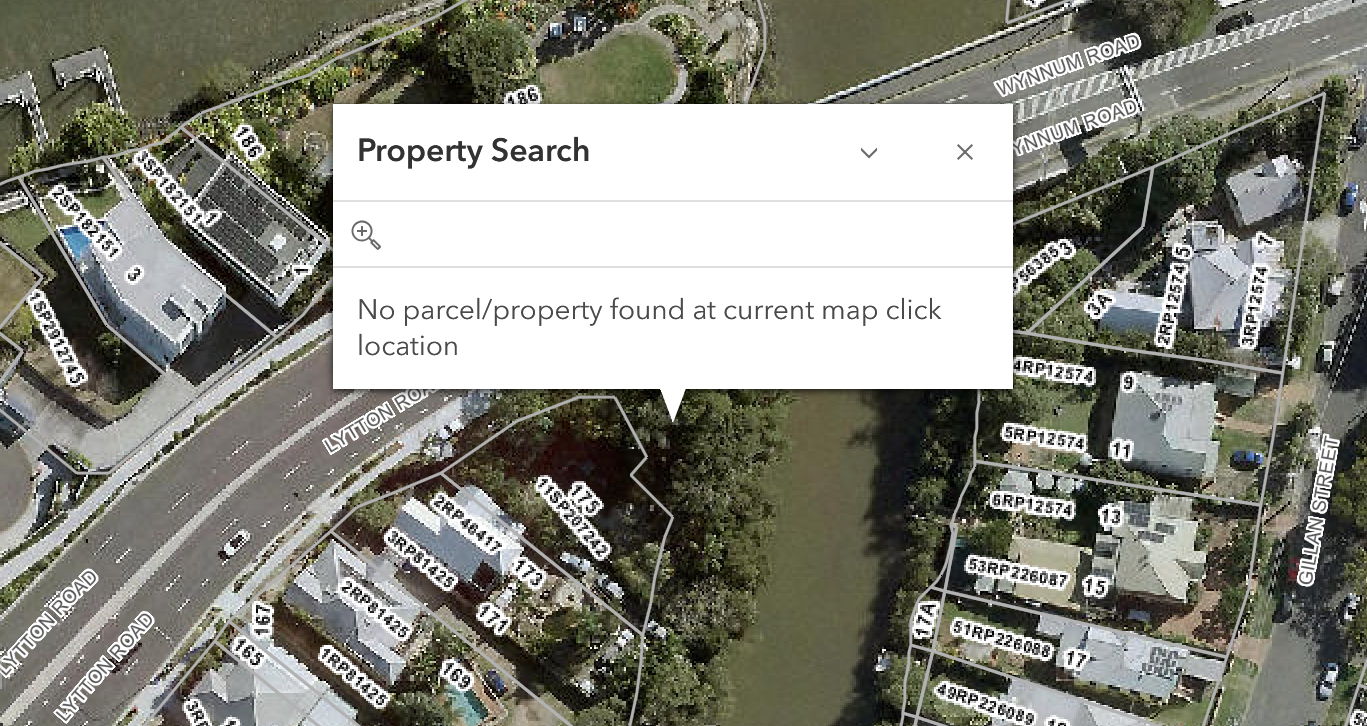

But in many parts of Brisbane, creekbanks and riverbanks remain untamed and unruly. And crucially, along tidal creeks, many of these slivers of not-quite-land are not officially mapped as lots under the state’s land title scheme. They’re effectively treated as being part of the public waterway, even if the upper slopes of the creek banks are only occasionally overwhelmed.

This yields important practical consequences for the way these places are controlled compared to other public spaces.

A neglected strip of land running alongside a train line or highway has a clearly-defined owner (as far as the colonial nation-state is concerned). The land might actually be a separate lot belonging to an entity like the Department of Transport and Main Roads, or it might technically be part of the roadway corridor itself (most roads in Brissie are owned and maintained by Brisbane City Council, with some state roads under TMR’s direct control). Either way, there’s a specific government department that eventually gets involved if, for example, someone builds a shack on it.

The same goes for city council parks. BCC has a bunch of local laws dictating what you can and can’t do in parks and bushland reserves, and staff with specific maintenance responsibilities for these green spaces.

But if a particular riparian green space isn’t part of a council park, or a roadway, or a separately titled plot of land, which government entity takes meaningful responsibility for it?

In practice: None of them.

Various organisations do have some responsibilities and powers over different aspects of Brisbane’s waterways (Maritime Safety Queensland, the Port of Brisbane, Healthy Land and Water, QPS Water Police etc.) and there are various environmental laws that – in theory at least – dictate what you can and can’t do. But most of those organisations put very little resourcing towards enforcement and regulation along the riparian zones of Maiwar and its tributaries. And the entity which most actively regulates and maintains most other public spaces around the metropolis – Brisbane City Council – is nowhere to be seen (at least along the lower, tidal reaches).

Unlike other public spaces, there’s no single government department saying, “this is our land and we’re in charge of it.”

It’s not that the government is wholly absent – just that you can get away with a lot more for much longer.

I tested the territorial extent of this responsibility vacuum with some guerilla gardening and revegetation work on the creek bank our housboat is moored alongside.

Growing veggies was challenging. The soil was salty, and possums, rats and bush turkeys regularly chowed down on new seedlings. But I planted several native trees and shrubs, and just above the minor flood level, I maintained a few pot plants with more resilient food crops like sweet potatoes. Eventually I added a couple large compost tubs alongside the pot plants, and even an old seat salvaged from kerbside collection. No-one cared. All that stuff sat there on public land, in plain view of anyone walking along the street, for years.

But one day, on the other side of the metal railing that roughly delineated the ‘land’ from the riparian zone, I placed a single medium-sized pot plant on what is technically part of the city council-controlled roadway. It wasn’t blocking moving traffic or pedestrians – it was tucked into the very edge of the street parking lane.

Within 48 hours, the city council had taped a note on the pot plant advising that its placement violated various local laws and it had to be removed (it was nice of the inspectors to leave a warning rather than just carting the pot plant away, but I imagine driving around with a potted sapling on their back seat for the rest of the day would’ve been more of a hassle).

48 hours. That’s all it took for the council to identify a single pot plant on the edge of the bitumen as a problem, whereas the pots and compost tubs in the riparian zone had been left alone for half a decade (meanwhile various caravans and boat trailers have been parked along the street for years, taking up way more space, but the council doesn’t mind because they’re registered vehicles).

At council-managed sites further out in the suburbs, guerilla gardening might go unnoticed for longer. But there’s always a chance that a mowing contractor or a parks officer or even a flood engineer is going to take issue with ‘unauthorised’ vegetation in a location that they believe should remain vacant lawn.

Whereas in the riparian zone, no-one from officialdom is on the ground.

The lack of regular inspections and active maintenance can be a boon for wildlife. Even council-owned habitat restoration areas often suffer from pseudo-science Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design ‘principles’ (I’m writing a separate article about how this entire field of design thinking is 90% bullshit), which recommend the removal of undergrowth and dense shrubs.

Along Brissie’s waterways, bushes and vines which would be torn out or trimmed aggressively in a council park are left to grow thickly, creating ideal habitat for numerous insect and bird species that are rarely spotted elsewhere.

I should note that this can have negative environmental outcomes too. On one occasion, I observed a wealthier property owner clearing a 10-metre stretch of mangroves from the publicly-owned riparian zone in front of their house (presumably to improve their water views) but I couldn’t get anyone from government to come out and enforce Queensland’s very clear mangrove protection laws.

On balance though, the biodiversity and ecological value of riparian zones along Brisbane’s under-regulated tidal creek banks is markedly stronger than nearby council parks of similar size.

The relative absence of government regulation can have positive ramifications for human life too.

On our creek, boat-dwellers negotiate among ourselves which spots seem safe to moor at, and what we should and shouldn’t tie ropes to. When someone new arrives on the waterway, looking for a place for their vessel, there’s no government authority dictating where they can and can’t drop anchor; we talk and decide collectively on locations that everyone feels comfortable with.

One poorly-secured houseboat coming loose in a storm could end up damaging or dislodging multiple vessels, so we're all invested in ensuring that everyone else’s boats are safe. In the lead up to heavy weather, boat neighbours check in on each other, offering practical help and emotional support.

Living on the water, I've gotten to know more of my neighbours on a more meaningful level than I did in previous homes on land. This was partly because most of them didn’t have full-time jobs, so there was more time for chatting and building relationships. And it was also because paying specialists to undertake boat maintenance is costly and difficult, so boaties have to rely more on each other for direct assistance with repairs etc. But the comparative absence of government in our lives is also a key factor.

If you're annoyed about a ceaselessly barking dog, or a vessel protruding too far into the navigation channel, you don't call officialdom to complain. You either talk to your neighbours about it directly, or you remind yourself that it's not really that big a deal and move on with your life.

This kind of direct communication can of course happen among neighbours on land too. But comparing my experiences living in many different parts of Brissie, as well as the dozens of neighbourhood communities I got to know through my work as a city councillor, communal connections and inter-dependencies in the riparian zone seem stronger by default.

When there’s no judge or umpire to complain and appeal to, people learn skills to work conflicts out among themselves. It’s still messy and imperfect. But it’s taught me that many of the functions we’ve been conditioned to rely on governments to fulfill can be handled directly by communities more efficiently.

The same might even be true for various safety regulations that limit how we manage and design our homes, but which add significantly to the cost and complexity of modern urban life. I’m more cautious about making broad, general claims here, as my sample size is small and there are lots of other factors at play. But riparian zone life has made me question whether all the different building codes and safety regulations that local councils enforce on land are entirely necessary.

Living on a houseboat, no-one else is ever checking, for example, whether your rainwater collection system is compliant with Australian safety standards, or is hazardous to drink from. You take on that responsibility yourself, research thoroughly, seek advice from others with experience, and decide what level of risk you’re personally comfortable with.

This might be a problem if landlords, property developers or some other profit-driven class were in charge of the design and maintenance of our floating homes – they would have financial incentives to cut corners even if it decreased safety for occupants. In a capitalist system, building safety regulations become necessary to ensure housing profiteers don’t make irresponsible decisions at the expense of their tenants.

But in Brissie’s riparian zones, boaties are mostly deciding for themselves how loose and wobbly their gang planks are, whether their internal staircases are wide enough, and where to place the fire extinguishers.

Many of us – myself included – have even learned to do our own basic electrical and plumbing work (this is less dangerous than it might sound, as we’re primarily working with 12-volt battery systems rather than 240-volt mains power – the risk of electrocution from dodgy wiring is much lower).

Not needing to comply with endless chapters of building code regulations and occupational health and safety rules is, quite frankly, liberating. We become more self-sufficient and empowered, which in turn translates to taking more responsibility for identifying and solving small problems before they become big ones.

It’s also a major money-saver. Setting up an effective, user-friendly compost toilet on a boat only costs a couple hundred dollars. But to install a compost toilet on land while satisfying all the relevant council and state regulations would cost thousands.

The relative absence of regulation means you can more easily trial, adjust and adapt new systems before you permanently entrench them. Rather than building everything to be rigid and cyclone-proof, you design stuff to be easier to dismantle and reposition as needs change, which often also works out to be more environmentally sustainable.

Even as they’re tamed and concreted over, these not-quite-land, not-quite-water fringe zones can remain spaces of free expression and counter-culture. Some of Brisbane’s coolest DIY gigs are found in drainage tunnels, as is a lot of the best graffiti. Being able to access urban land without paying a fee, filling out forms or taking out public liability insurance allows artists and event organisers to take risks and push boundaries just that little further.

Why does all this matter?

In such a controlling, heavily-surveilled city, less-regulated liminal spaces like creeks and riparian zones are still serving as laboratories for ethical, sustainable living. Residents can experiment with different ways of maintaining homes and relating to each other, trialling unorthodox approaches to social problem-solving, climate adaptation and genuine resilience-building. This is something that should be celebrated and valued.

Living in a world that’s wilder and looser than conventional urban and suburban neighbourhoods has broadened my imagination about the ways shared spaces – and indeed, entire cities – can be redesigned and transformed. When an internalised finger-wagging government official in your subconscious isn’t pressuring you to preemptively self-censor your ideas, radical possibilities start to germinate and multiply.

The word ‘freedom’ gets thrown around too carelessly these days. And while in the riparian zone, you’re certainly not free from the impacts of global warming, life does feel a little freer in general. The nation-state doesn’t even have an accurate estimate of how many people are living on Brisbane’s waterways. Census data doesn’t capture it properly, and it’s not like people have rates accounts or water bills or rental bonds lodged with the RTA.

In a city that tends to present most residents with a fairly narrow range of options for how you can live... cookie cutter suburban sprawl, concrete jungle highrise... the fact that people still exist on the margins – living out happy, healthy lives without boundary fences, leases or title deeds – is a subversive reminder that other, less-constrained futures are possible.

Once you’ve experienced life in these kinds of liminal spaces, anarchist proposals for societies without states and hierarchical rulers start to seem much more reasonable and practically achievable (Graeber and Wengrow remind us that such societies have existed in many regions throughout history, and not just among 'small groups of roving hunter-gatherers'). You know it’s possible for people to coexist – and even to agree upon and abide by rules and norms for living in close proximity to each other – without the need for guns, gavels and governments, because you’ve had a taste of it first-hand.

I don’t want to overcook these claims. Title deeds or not, we’re still settlers on stolen Aboriginal land. It’s certainly not the case that the narrow stretches of densely-vegetated creek corridors snaking through Brisbane’s suburbs are beyond the effective control of the colonial nation-state, or that the loose networks of a couple dozen boaties living on Brisbane’s waterways are anarcho-communist separatists existing entirely outside the capitalist economy.

But even the feeling that the government isn’t breathing down your neck is kinda liberating. It changes how you see the world.

I’m cautious that sharing these observations publicly is a little risky. Highlighting the current limits of government control and data collection risks drawing the attention of Sauron’s unblinking eye, so all this is intentionally a little vague. But I think it’s important to remind more Brisbane residents that nuclear families, intercom security systems, 30-year mortgages and neo-feudalist landlords need not mark the limits of our imaginations for urban life.

Riparian liminal spaces are only a small part of a modern city’s urban footprint. But what if we took some of these lessons and practices beyond the top of the creek bank, and spread the anarchist zone of influence a little further?

Thanks for reading! If you have more questions about this, feel free to post up in the comments and I'll try to answer when I have a spare moment. And if you enjoy articles like this, please consider subscribing to help me carve out the time to write more often...

More on houseboat life in this article...

Member discussion